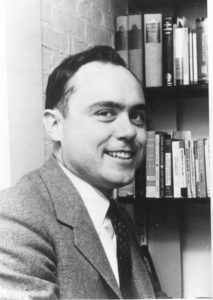

Robert L. Gaudino

Robert L. Gaudino

My impressions of Robert Gaudino were formed when I took several of his classes and experienced the extraordinary way he taught. I later served as a Trustee on the Gaudino Memorial Fund, founded by my brother Richard ’60. A character in my novel, Not Our Fathers’ Dreams, includes a character who is drawn from Bob, with much reverence and awe. It was under his prodding that my first experience after graduating was to join a domestic Peace Corps-like organization that got me teaching in Lower Manhattan, a profound experience that has remained with me all these years, giving me, as he would have wanted, a greater understanding of other lives and cultures than the one I grew up in.

Robert Gaudino was the smartest man I ever met. Short, yet he filled space and conversation and thought with the immensity of his intellect. He seemed always turned on, plugged into a higher voltage source, crisp neat hair over big eyes. It always appeared as if he was moving forward, intense yet inclusive, focused yet expansive, devastatingly astute yet with a gentility that encouraged participation even as you knew you were going to get skewered.

Gaudino loved it when students brought new perspectives into the classroom, disparate disciplines. He smiled, a broad gesture that encompassed his whole body, he almost shook with delight, moved forward.

One showed up for Gaudino prepared for class! There was no moment on campus more alive or terrifying than the one in which he turned his entire compact frame towards you and asked you a question, no instant more rewarding than listening to his dissection of your now feeble-sounding answer.

Talk in the classroom flurried, a cacophony of the best and brightest pack ferally running down an idea, under the spotlight of Gaudino’s gaze, which encouraged, demanded their best performance. Then he did his usual summing up, somehow weaving in Socrates, Schopenhauer, Hegel, obscure French resistance philosophers, the Social Contract, the Beatles, Fellini, a border dispute between India and China, and an editorial in the Williams Record regarding the responsibilities of free speech. I lived for these class moments, a final five minutes in which Gaudino found and expounded a coherent thread amidst the seeming chaos of class discussions, knitting it all together into a clear narrative, placing what each of them had said into a panorama greater than they could see of themselves, briefly enabling each of them to understand that when they spoke they were representing context, background, and perspectives, understand that in a way larger and deeper than they would ever again realize in their lives.

Characteristically, Gaudino might say something like, “The truths we hold to be self-evident turn out to be personal.” When he said something like this, I thought he was looking directly at me, into me. His epiphanies were like moments of stoned clarity — overwhelmingly clear and important in their instant, impossible to retain.

Gaudino could see people in their place without putting them in their place, a piercing combination of insight and gentility. His bright eyes sparkled, he leaned over, barely clearing the table yet filling the room.

He dared venture into the classroom where no other professor would go, to the core of your beliefs, to exposing the assumptions that came from Shaker Heights or Atlanta, Santa Barbara or even Brooklyn, propounding that there was an intricate but massive connection between the visceral and the intellectual, the personal and the political, and it was his mission to explore and examine it, shine a bright intellectual light on what more typically lay in the emotional dark. Gaudino had a unique capability to enter this arena of self that other professors and conventional academia shied away from.

He was always smiling, always on. Sooner than later he’d say something you didn’t understand, but he did it in a way that still made you feel included. Intellectual non-violence. In discussing the very pertinent to us issue of the draft, he said, “Identity driven pluralism foments a challenge to power posing as authority, where license has replaced legitimacy.” We just nodded. We couldn’t understand how he did it, much as we wanted to emulate it; we saw the Olympic medal run without the thousands of hours of training behind it.

Professor Gaudino knew more about everything, who could imagine great visions with his eyes open, who seemed to see us better than we saw himself, but wouldn’t just give us the answers, he forced us to a realization of the questions. As he said, “There are more possibilities in action than in theory.”

Gaudino had a way of looking that seemed to encompass you, the room, the world at large and the biggest space of all, inside his head. His brand of political science was so different and controversial that the College had initially denied him tenure, then bowed to a huge outcry from his students.

In one of our snack bar gatherings, someone asked about Antonioni’s Blow-up. Whether there really was a tennis ball in the closing scene, in which people mimic playing. Everybody had their say, each a different take, most agreed there was not.

“Of course there was, otherwise the entire movie didn’t make sense,” Gaudino said. Well, a good part of the movie didn’t make sense to us anyway.

“Naturally,” he said, “a Marxist like Antonioni professes to be would explore private discourse in the context of purported total freedom, swinging London, showing the underpinning of moral confusion in a democracy through the inability to distinguish between fantasy and reality.” Everybody nodded. (Imagine how much we could use his insight now).

If I were back in school, I would go to the snack bar to search for answers, or at least the solace of exploratory discourse. Grab a sticky bun and double large iced tea, join the group that always gravitated around Gaudino, ensconced in a booth near the windows, pulled by the mass of his intellect, warmed by the gentle urbanity of its expression.

I wanted to be like Gaudino, always turned on, in love with each moment and each day.

Robert Herzog