“There’s nothing I’ve ever experienced in my life that hasn’t appeared in a cartoon,” David Sipress was saying.

The evidence is in “What’s So Funny? A Cartoonist’s Memoir,” which vividly illustrates how art can spring from angst and serve as a kind of therapy for the creator and the reader who shares the experience.

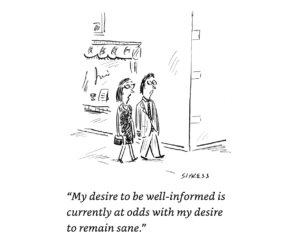

Who can’t relate to David’s most quoted, reprinted and shared cartoon, from the mid-1990s?

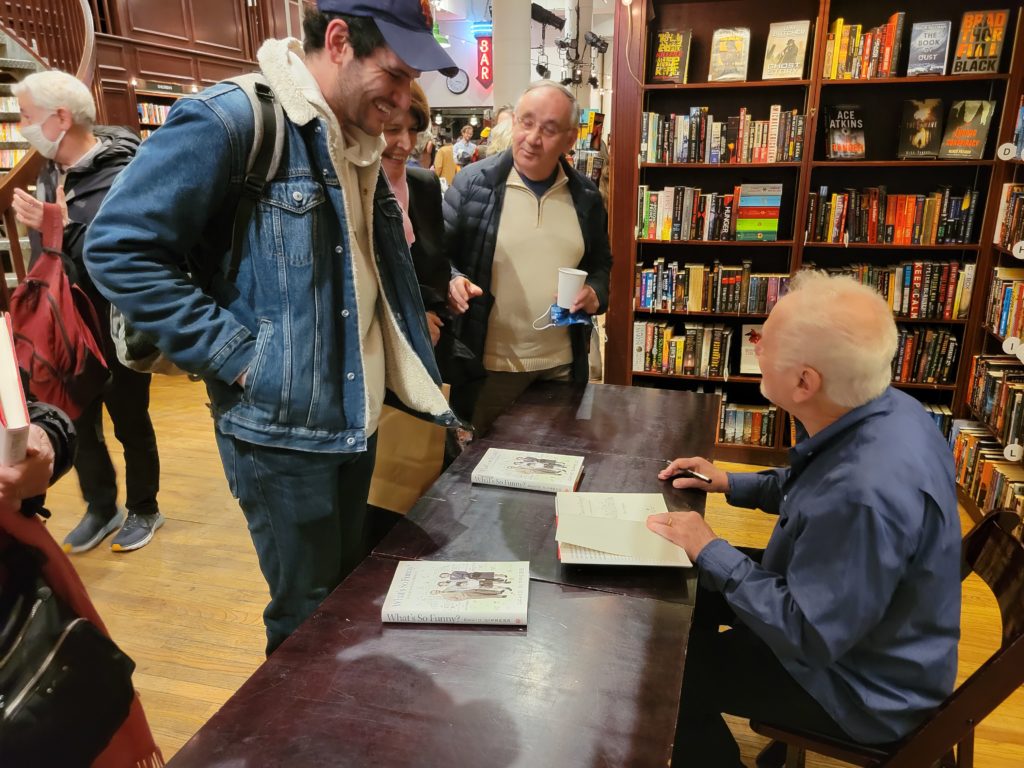

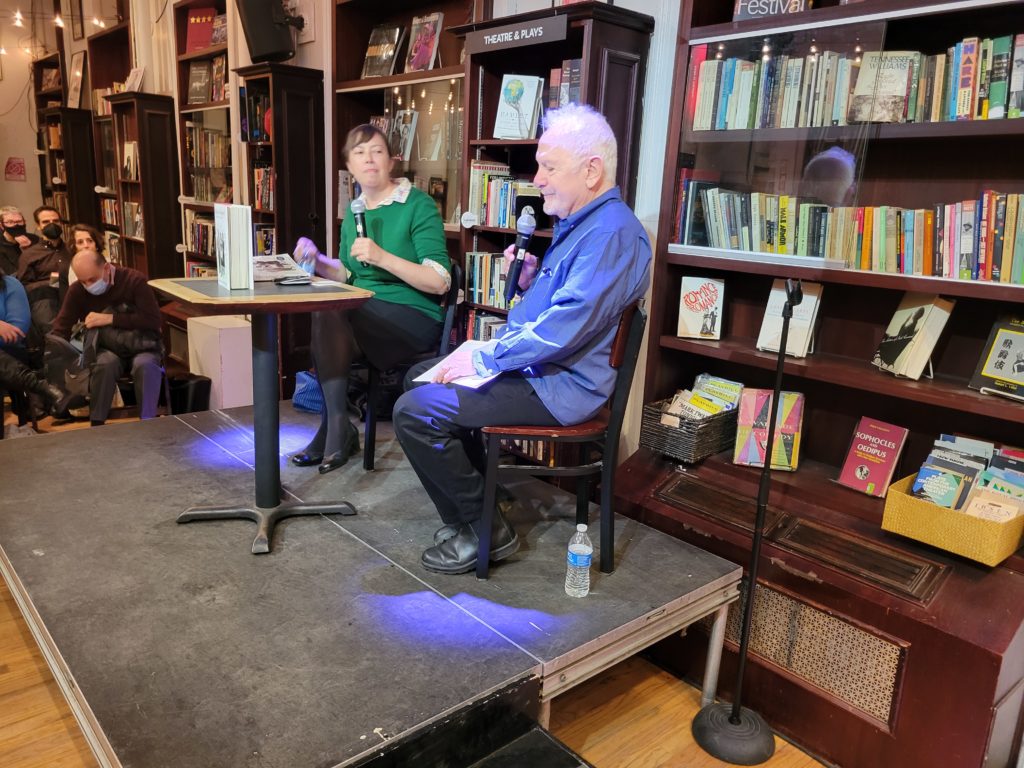

Two days after April Fool’s Day, at a book party at the Housing Works Bookstore in Manhattan’s Soho, David was reminiscing on a platform with Sarah Larson, a friend and New Yorker staff writer.

(In 1990, David’s wife Virginia “Ginny” Shubert founded Housing Works, a pioneering nonprofit serving New York City’s homeless men, women and children living with HIV and AIDS.)

“In cartooning, there’s The New Yorker and everything else,” David was saying. “It took me 25 years to sell my first cartoon to The New Yorker.” Since then, he has sold more than 700 cartoons to the magazine.

But that first cartoon wasn’t published right away, and perhaps nobody was more impatient to see it than David’s father Nat Sipress, who never really forgave his son for dropping out of Harvard graduate studies in Russian history to become, of all things, a cartoonist.

Issue after issue went by, and no David cartoon. Then Nat died.

“Note to any cartoon editors here!” Sarah interjected. “Publish a cartoon timely!”

“It’s a matter of life or death,” David added.

As it happened, Nat had emigrated in 1914 at age 8 with his family from Medzhybizh, a village in the Ukraine, then part of Russia. Medzhybizh, west of Kyiv, now under threat of attack by Russian forces.

Nat made a success as a jeweler on Manhattan’s East Side, and David was mainly raised in “Mrs. Maisel”-like circumstances on the Upper West Side. The memoir describes an epochal, oedipal struggle between father and son with which many of us can identify. (David turned to therapy, and an unnamed therapist gets an acknowledgement in the book). In Nat’s capacity for suffering, and his appreciation for what he called “beautiful things,” David had an epiphany.

David credits his mother Estelle for his talent as an artist and his sense of humor. But Nat may have given him his edge.

David briefly mentions Williams in a tale of his clash with a Bennington security guard 20 minutes from the midnight curfew.

“My cartoon brain never shuts off,” David was saying at Housing Works. Sometimes a situation and a caption come together in an instant. But one drawing hung captionless above his desk for years.

Then one day he looked at the drawing and added a speech balloon — “a gift from the cartoon gods,” he calls it.

An occupational hazard of cartooning are the New Yorker fact-checkers, who review content and caption.

In fact, once David drew an animal sacrifice in ancient times.

“The fact-checkers pointed out the sword is double-edged, where the custom was single-edge,” David recalled. “And the temple behind the goat had five columns when the number of columns always had to be even. Those were their corrections.”

David paused with just right sense of comic timing about life’s absurdities and how he sees them, “I told the fact-checkers, ‘But there’s a talking goat. Why didn’t you have a problem with the talking goat?”

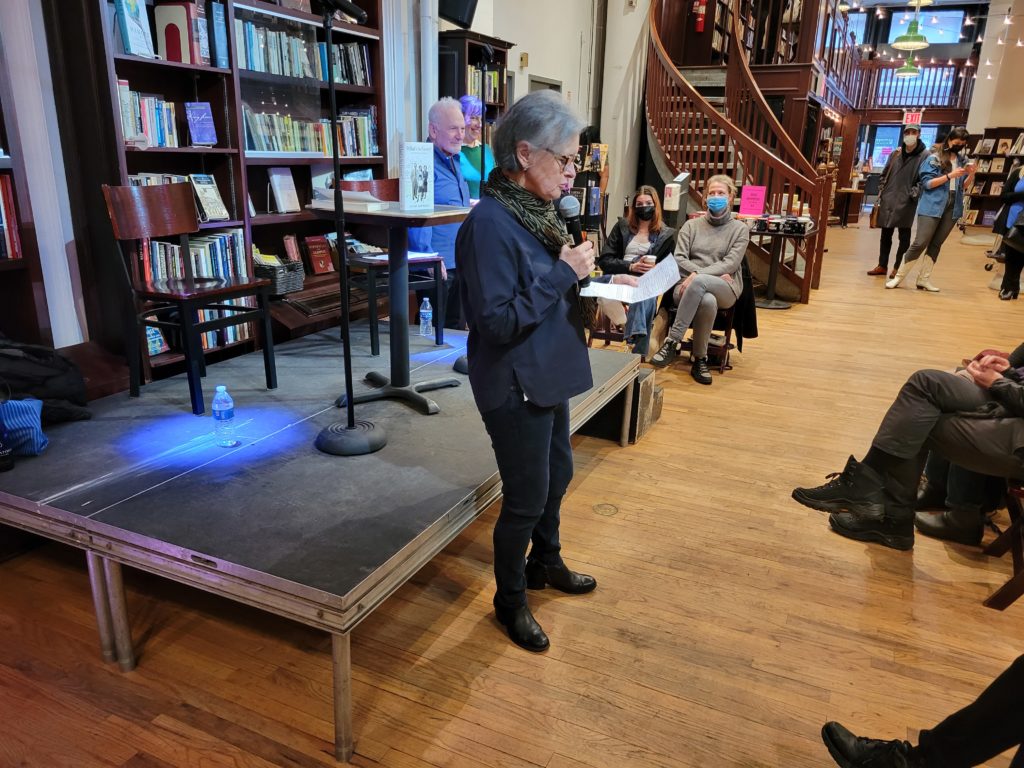

At the Housing Works Bookstore on Sunday, April 3, Virginia (Ginny) Shubert, David’s wife and a co-founder of Housing Works, introduced the proceedings. The “What’s So Funny?” frontispiece says, “For Ginny.” David told the crowd that his demeanor is owing to “therapy and cartooning and the great Ginny.”

“The humor in the cartoons has to do with something that readers feel in themselves,” David said in response to a question from master of ceremonies Sarah Larson, long time friend and New Yorker staff writer.