To Finish a Book

To Finish a Book

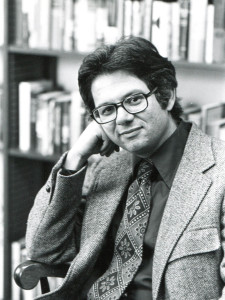

Charles Samuels was a professor of English and of Film Studies at Williams College in the 1960s and part of the 1970s. He was, by near all accounts of former students, a terrifying presence in the classroom – not maniacally nor physically nor in volume but in intellect, in rigor and in relentlessness. To a loner, as I was, he was a sharper, clearer edge than I had ever seen or imagined, a force of other nature. He read books with an almost gleeful ferocity and it took no moment to realize that I was moving not too slowly but in truth not moving. I was a tourist to reading.

Samuels was a Brooklyn native, a graduate of Syracuse (B.A.) Ohio State (M.A.) and Cal Berkeley(PhD) a Phi Beta Kappa and he came to teach at Williams in 1961 as a 25 year old. Williams was proud of its English Department – they were a little surly, irreverent, and wry. Many of them smoked and peered, and poked and laughed with some profanity and they knew Chaucer and Milton and Joyce and they knew that none of them was an angel. They drank and loved food with more than decorum and they were all a little tweedy. Williams is a tweedy valley.

Samuels was not tweedy. When he smiled, part of you got nervous. When he looked at you, all of you got nervous. He had terrible skin, some of the time.

We handed in our papers like an unemployment line. When he responded (he did not always respond, sometimes the paper simply disappeared), he would begin at the first sentence and trail you to the very end and beyond, in a small, tight script, tracking your thought, your structure, your attempts and your grammar. You took these corrected papers to your own corner – they were you, dissected. If, in that jumble of your mess and his tracking there should appear a correct or a good or a very good, then you were indeed a happy soul.

We took notes, in part to keep up but more to keep at bay our fears of falling behind, being exposed as tourists or falling completely overboard. It was clear, if you went overboard, the boat was not circling back to pull you in. It was not that there was no sense of care or concern – it was simply that the ferocity was so primary that it might be a while before anyone noticed you were not there.

For diversion and action and pleasure, Samuels would turn his full analytic attention toward the cinema. His heroes – the Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni, for example – were his perfect opponents, equally fierce and relentless, righteous and passionate, present with their mind and their heart at every moment, every frame. A mythic match, in a field where few had brought such weaponry.

I had no idea, nor even image, that you could see a film with such intensity, that you could look and hear and feel such detail, that its construct had in every sense been intentional and literal. It was the 60s, so the air was filled with minds going off in many directions and Samuels was gleeful with the tasks of finding the brilliances and casting out the fools and frauds.

In 1974, to many peoples’ surprise and deep sorrow, Charles Samuels comitted suicide in Williamstown, leaving behind his wife and their young daughter. I do not know any of the circumstances.

But I have imagined what might have been, had Samuels not had such a tragic turn and remained at Williams for a full career. I have even imagined a specific and mythic collision of Charles Samuels and three contemporary business titans – Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos, imagined freshmen at Williams, forced by requirements to take English 101. ( None of them actually went to Williams and Bezos is actually nine years their junior)

A Completely Imagined Meeting, in the Chapin Library office of Professor Charles Samuels, year perhaps 1975 or so.

Gentlemen, I thought a meeting might help to clear up a few matters, regarding your performances in class. I am sure you each imagine there are more important things to do than to excel at English 101. This is a school of many strivers and you three obviously stand out in that regard, a detail that is only partly a compliment. But you are not striving for very much in my territory.

Mr. Jobs – you, for example, had the specific task to read 400 pages of Henry James, in a week. It is clear you have read no more than 30 pages, rather intently but 30 pages nonetheless. You reported that they were brilliantly designed and I agree but you seem to have fallen on the sword of their craft and not been able to move at all past. There is the book itself ahead, the brilliance is the brilliance but it is even more brilliant that it is but a part of the whole. No one writes with the craft of James and once realized, it is difficult to not forever be pleased with that craft but you must take into account the incredible effort that it must all matter. The craft and the design, but the humans and the consequence and the spoken and the silence.

Yours is an interesting Dickensian name, Mr Jobs, and it shall be worth keeping track as it unfolds with your life and your career, should they involve jobs, won and lost and , of course, Job, the most difficult of debt and trials.

To you Mr Gates, I must say that you have done a rather intensive analysis of The Sound and the Fury, deep into its construct and history and you have obviously made a great attempt to understand it all. Most remarkably, you have taken everything into account except the sound and the fury, except the passion and the agony. You have missed the South, you have missed William Faulkner and you have missed the soil of this book. I do not know how you have done this and not gotten any of it on you but that is the case.

And you, Mr Bezos, you have done the strangest work of all for you have not read the book. Do you even like books, Mr Bezos or are they too messy for you ? You have written about the foolishness of commerce, the waste and mishandling of so many details left to labor and chance. Is it really your vision that our best course is to clean and simplify, to let people pull back from the layers of time and dirt and error and be delivered to, that our hopes are with screens. Have you watched people watch television ? it is not an act of spirit – you may perhaps need a little time with the Italian films. They know about alienation, they know about modernism, they know about concrete and nameless work and the death of spirit – you should visit the films of Antonioni and feel the blood of a people who will not be drained.

But enough, gentlemen. Let me say that you shall each likely be a great success but let me ask you, at what cost ? Do you know the phrase, Too clever by half , – you should keep it in mind. At one time, it was the skewer of skewers to be so described and no man wanted that skewer sticking out his ribs. But these are sterile times, of both culture and education and clever seems near a virtue now.

You are each too busy to read. You are each important characters, in a kind of Roman forum, but, contrary to what you might imagine, you are probably not the play, you are only characters. You are not the passion nor the reason – you are only the brokers. With luck, the course shall be set by a greater humanity. And, with luck, your work shall lead you to a chance to join that humanity.

It was the brilliance and fate of Charles Samuels to hold a line.

Many students went out of their way to avoid his review. There is a report from one of his students that upon hearing of JFK’s assassination on that Friday in November, Samuels screamed at the four walls of his classroom.

Salut, Professore, salut!

Peter Miller

Editor’s note: Peter is not the only classmate to remember Charles Samuels. Barton Phelps recently sent us his own recollection which follows here. Note to classmates: there is no limit to the number of tributes we can write and post here for our classmates. Any others for CTS? Send email to webmaster at williams68.org (replace the “at” with the “@” sign.

Here are Barton’s words:

Basic Classroom Training

Years of academic experience have only increased my admiration for the gentle, brilliantly humanistic teaching that characterized the redoubtable Williams Department of Art in the 1960’s. So appealing were those courses that, as a pre-med student, I chose to major in art, a decision that ultimately led me to do architecture and not medicine. That move’s immeasurable benefit to humanity notwithstanding, the most effective and memorable instruction I received at Williams was from Professor Charles Thomas Samuels in English 208, Spring Semester, sophomore year. I now realize how lucky I was to undergo Prof. Samuels’ extraordinary, (pre-deconstruction) version of a standard, introductory survey of modern American literature. Secretly, a few of us referred to him by the nickname, “Charlie” – I think because it made the intellectual persona seem a little less scary. That initial response may be partly why the words and sounds of Samuels’ startlingly unmodern pedagogy still resonate in my head.

The Samuels method, we learned, combined a lightning-fast and frightfully demanding form of Socratic give-and-take with what seemed to me to be unobtainably elevated expectations for deep reading and limpid exegetic writing. Soon it became clear that Samuels’ responses to our efforts would transcend “hard grading” as we had known it heretofore and you could tell everybody was terrified.

I’d never had an academic experience quite like it, nor have I since but, looking back, I see certain similarities between that semester-long class and a later ten week-long “required” learning experience that, in the U.S. Army, is called Basic Combat Training. I doubt Samuels had any interest or experience in the military but, interestingly enough, both his instructional method and the Army’s entailed restructuring unacceptably relaxed mentalities to respond quickly to particular stimuli. Both demanded complete subrogation of trainees’ personal thoughts to those of the Leader. Both operated with unexpressed but commonly understood rules.

Both also took the rapidity and clarity of responses to the Leader’s questions as reliable indicators of adequacy in preparation. People did the reading all right, but in Samuels’ class one had only a few seconds to begin to answer his question or the chance vanished, instantly redirected to the guy sitting next to you in what I seem to remember as a directionally unpredictable orbit around the seminar table. I can still hear that surprisingly big voice as it politely offered and then promptly withdrew the chance to respond: “Mr. Goolrick?… Mr. Jones?… Mr. Thompson?… Mr. Phelps?…” , etc. Especially relevant BCT memories in this regard include Bayonet Training first thing in the morning and the shiny wood bench at the Grenade Range polished by countless Trainees sliding along awaiting their scary turn in a din of explosions and hailing shrapnel.

Classroom discussions were stimulating, evoking a sense of closeness to the era of each author, their thought patterns, writing styles, techniques and creative leaps and, in that room, literature was the most important thing in the world. The classes were very tense. Samuels could be witty but I have no clear memories of having fun. His questions mostly regarded correct understanding of essential textual meanings and the sessions were unabashed canonical exercises in right and wrong. Brevity in answering was highly valued. Overly long responses were interrupted and personalizing interpretations immediately cut short. A correct answer, should one occur, was greeted by a slightly excited, greedy-sounding, “Yes, and what else”? To get two or more correct answers in a row was to triumph and, as I assume Samuels intended, people began keeping score. The whole thing proceeded at an amazingly fast clip but, somehow, the hour elapsed slowly. Almost every session was gut-wrenching and we were thrilled to step out into the fresh air when it was over. (Think: the firing line on the Bazooka Range followed closely by the Gas Mask Test.)

Weekly paper assignments required more complex answers but the classroom canon held. Hard wrought, thoughtful responses, if seen to be overly creative, could elicit low grades and such helpful comments as labeling the student’s answer, “A vulgar evasion of the question.” Rules for weekly papers limited length to two pages, double spaced and it didn’t take long to realize that responding fully to the assigned text was next to impossible in anything approaching proper English. Although he never said so, I’ve always wondered if Samuels actually intended for us to experiment with the flexibility and declarative power of the language or whether he valued the discipline of the struggle to stuff it all in with its risk of receiving a frontal, summary comment like, “This is very poorly written.” In grading papers, he enjoyed using editorial marks like “AWK” for awkward wording or another I’d not seen before – a large, loopy “S” which indicated, he cheerfully explained, “Sentence beyond repair”.

The experience that brought me closest to understanding “Charlie’s” extraordinary gift as a teacher was the analysis of a pivotal moment in “What Maisie Knew” by Henry James. After many drafts, my paper was still too long and it had to be ruthlessly thinned and hacked up in order to fit. As the graded papers were returned I could hear soft groans of disappointment from some of my classmates. Samuels said nothing as he handed the two sheets to me but I could already make out on the first a large loopy “S” and an “AWK” or two. Similarly marked up, as I then saw, was the other sheet. Anticipating complete failure (the dread B – or worse), my eyes dropped to the margin at the bottom of the too-full second page. Printed in bold pencil letters and with no explanation it simply read, EXCELLENT. It was only then that, to my disbelief, I noticed, at the top of the first page, the letter, A.

Barton Phelps