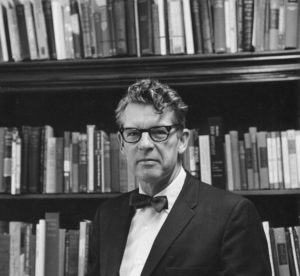

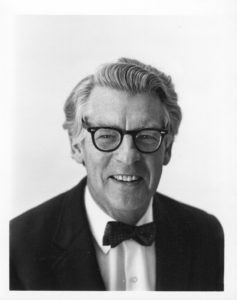

Perhaps Fred Stocking was not as passionate or flamboyant as Clay Hunt. Perhaps he did not possess the intimidating intellect of Charles Samuels. Nor did he command the immense treasury of knowledge of Don Gifford. I enjoyed my classes with each of those men. And Hunt and Samuels didn’t hesitate when I asked them to write recommendation letters. But, for me, Stocking made all the difference. Always dapper in his bow tie, Stocking was approachable and dependable, inspiring and energizing, convivial and comprehensible. For me, he was that guy on the other end of the log

Perhaps Fred Stocking was not as passionate or flamboyant as Clay Hunt. Perhaps he did not possess the intimidating intellect of Charles Samuels. Nor did he command the immense treasury of knowledge of Don Gifford. I enjoyed my classes with each of those men. And Hunt and Samuels didn’t hesitate when I asked them to write recommendation letters. But, for me, Stocking made all the difference. Always dapper in his bow tie, Stocking was approachable and dependable, inspiring and energizing, convivial and comprehensible. For me, he was that guy on the other end of the log

Fred Holly Stocking, who became the Morris Professor of Rhetoric at Williams College, was born in Detroit, Michigan, in 1915. He graduated from Williams in 1936, and entered the Ph. D. program at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. After successfully completing his oral exams, and while working on his thesis, he returned to Williams as an instructor and taught “in the V5 program, training navy cadets in flight navigation and Morse code, as well as in the V12 program, teaching naval officers a liberal arts curriculum.” [Stocking, Fred. “Oral History Interview,” Williams Special Collections.] In 1946, with WWII over and his Ph. D. thesis accepted, Stocking was hired as a Williams professor, where he inspired and instructed thousands of students until his retirement in 1983. I have no doubt that Stocking’s years of practical experience teaching navy cadets during WWII helped him develop his convivial, convincing, classroom-friendly teaching style.

Stocking’s endowed chair at Williams, naming him the “Morris Professor of Rhetoric” might make him sound old-fashioned. After all, when people use the term “rhetoric” today, it is usually synonymous with bombast or pomposity. But to the Greeks and Romans, and to Stocking, rhetoric was the art of instructing, entertaining, and moving listeners. Stocking was an expert at this, and if you need any reminder of his persuasive skills, take a look at his 1970 article “What’ll We Do?“in The Williams Alumni Review, where he discusses using Paul Simon’s “Dangling Conversation” as a paper topic in his freshman English class. Not only does he provide a thorough and respectful explication of Paul Simon’s lyric as a poem, but he goes on to talk about how having been schooled in songs such as this, the so called “protest” generation of the 60’s might have much to teach its elders. He was proud of us, and he was one of us.

Using a little rhetoric of my own, let me state that I owe my success as a student and my career as a teacher to Fred Stocking. When I was a Williams student, Professor Stocking helped me discover the special magic in Shakespeare. When I needed guidance for my Honors presentation in English, he coached me. When I needed recommendations for M.A. or Ph. D programs, he enthusiastically wrote letters. When I needed my first classroom teaching position, he landed me the job.

Stocking’s first, simple gift to me occurred in an afternoon Freshman literature class, when we were studying Shakespeare’s 1 Henry IV. I should be really honest here. At that point in my life, I’d never seen a Shakespeare play actually dramatized on a stage with live actors. I loved the Shakespearean language as poetry, but I really didn’t understand what all the fuss was about. To me, Shakespeare’s language was like a museum exhibit of exquisitely displayed, but inert fossils. As an essay assignment, Stocking had asked us to analyze the scene in Act II, scene iii, where Hotspur receives a letter informing him that one of his fellow rebels is backing out. Trying to highlight what we had missed in our essays, Stocking emphasized the drama of the scene by reading Hotspur’s lines and shaking his lecture notes as if those yellow sheets were the rebellious rebel’s letter… maybe even the rebel’s neck. Stocking was not delivering the usual “discursive” lecture about stage business reinforcing the text. Stocking acted out the scene. He wasn’t telling us what happened, he was making it happen again.

Now, Fred Stocking was no Ralph Richardson, and all his students will recall his slightly nasal Midwest accent that was imbued with a special Stocking cadence. Nevertheless, his dramatization of that scene with Hotspur shaking the rebel’s letter helped me realize that Shakespeare was words combined with action, not just words. Shakespeare wasn’t beautifully dead; he was wonderfully alive. That was a moment of real discovery for me. Out of all the literature classes I’ve attended in my career as an undergraduate and graduate student, that Hotspur re-enactment stands out. And if, in my own modest career as a teacher, I tended to “act out” too many scenes, all the credit should go to Professor Stocking, for setting such an alluring example.

Although I didn’t take a lot of classes from Stocking, when I became a senior, he happily agreed to be the chair of my Honors Committee. In my naive ambition, I was determined to reveal the mysteries of Thomas Pynchon’s recently published short novel The Crying of Lot 49 to a panel of tenured, published, Williams professors. Stocking was willing to help me navigate this final, potentially tricky landfall to my academic studies at Williams. In fact, near the end of my presentation, which had gone pretty well for fifteen minutes or so, he saw me struggling to describe a key plot point, where several Pynchon themes reached a climax. Despite weeks of worried preparation and a sheaf of notes in my hand, I got all tangled up among the conflicting motives of Pynchon’s menagerie of postmodern characters– the flighty heroine Oedipa Maas, her stolid husband, the used car salesman turned radio DJ, “Mucho” Maas, her treacherous psychotherapist Dr. Hilarius, the mysterious stipulations of Pierce Inverarity’s Will, and the sinister, underground Tristero group against which they were all contending. Sensing my desperation, and looking at his watch, Stocking concluded, “Well, Mr. Thomas, the way you’ve described it, Pynchon certainly does seem to have made the characters all come together.” His life-saving pun provoked laughter from me and the faculty panel.

Two years later, after I’d gotten an M.A. from UCLA (thanks to a persuasive letter of recommendation from Stocking) and was trying to relocate to Williamstown for a while, Stocking landed me a job at The Pine Cobble School. For two weeks, with a brand new M. A. diploma in my possession, I had been working humbly in the basement of the Stetson Library, in charge of two brand new Xerox photocopying machines. One afternoon, walking across the vacant lot that stretched between Stetson and Baxter Hall, and along the backside of the Congregational Church, I ran into Stocking. He remembered my name and asked how I was doing. The next day he actually came to the Xerox room and told me he’d heard that Pine Cobble School needed a new English teacher. He’d recommended me to the director, whom he knew quite well. So that’s how he launched my classroom teaching career. I’m sure he would have done the same for any qualified English major, but he did it for me, and that made a big difference.

In the two years I taught at Pine Cobble, which was temporarily housed in the basement of the Congregational Church, I occasionally ran into Stocking as he crossed from the Stetson Library towards Baxter Hall. He made sure I understood that he was ready to revise his letter of recommendation when I wanted to enter a Ph. D. program.

I remember one of the last times I saw Stocking was in January of 1972, purely by accident, when I showed up for the GRE Exams, and he was the proctor. I felt that I needed a good, even perfect, GRE English literature score to get into grad school. But, at the end of this three hour ordeal, there had been one question on the exam that puzzled me. So, after the paper booklets and the scantrons had been handed in, and Stocking was organizing papers at the front desk, I approached him, said hello, and asked, “Was that quotation, ‘Poetry is the supreme fiction, madame’ written by Wallace Stevens?” Professional to the core, Stocking knew he couldn’t actually tell me the right answer. Instead, he smiled at me and said, reassuringly “Thomas, you’ll do just fine.”

I did do just fine, and it was thanks to Stocking’s efforts. My teaching career had begun with the job Stocking obtained for me at the Pine Cobble School, and his letter of recommendation (along with my nearly perfect GRE score) surely helped me get accepted into the Ph. D. program at SUNY Binghamton, which led to my hiring as a community college instructor in Los Angeles, and a career that lasted 35 years. And that once puzzling quotation from Wallace Stevens, “Poetry is the supreme fiction, madame,” seems a perfectly appropriate epigram for any English teacher’s career. Fred Stocking spent his life helping students enjoy the supreme fiction of poetry, and, thanks to his efforts, so did I.

Once I was launched into my Ph D. studies at SUNY Binghamton, I regret that I never contacted Stocking again. I didn’t let him know when my thesis was accepted. I didn’t inform him when I got my first, really permanent teaching job. But, maybe I didn’t need to. He’d already done his job. When I needed his help, he’d gladly offered it. Once I was successfully launched on the supreme fiction of my career, he didn’t have to worry about me anymore. My hunch is that Stocking helped thousands of students like me pursue their graduate studies, launch their careers, and enjoy the ways language helps us understand the world around us.

Lloyd Thomas