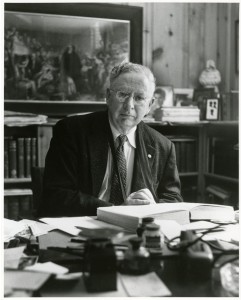

Richard Ager Newhall

Richard Ager Newhall

Our freshman class, arriving in the fall of 1964, contained an exceptionally large number of history students. This seriously overtaxed the resources of the College’s history department, and reinforcements were brought in to meet the demand. One was a legendary, retired professor, Richard Ager Newhall. He had last taught at Williams eight years before, but he had remained active by teaching for one year thereafter at Colby, and later at the Pine Cobble School in Williamstown. In 1964-65, he taught European history to some of us freshmen at Williams, and also provided Advanced Placement instruction in European history to students at Mt. Greylock Regional High School. He was then 76 years of age, but his love of teaching and his faculties were clearly undiminished.

One could not help noticing immediately Professor Newhall’s physical disability—the shoulder sling he wore to support his injured arm, and the glove on his hand. Word spread that he had been severely wounded in World War I. The speculation was that he had probably been gassed. I do not recall that he ever referred to his war injury in class. Certainly he did not allow it to interfere with his classroom activities.

Every class began with a short exam. This traditional means of ascertaining whether one had read and understood the assigned material quickly instilled proper academic discipline in us. He used the discussion of the day’s quiz question as the jumping off point for a lively exploration of the particular political, economic, military or religious developments we were studying.

Professor Newhall’s style of delivery was not flashy or dramatic, but his obvious fascination with the sweeping movements of the past, as well as the foibles of human behavior, was infectious. He also had a playful wit that enlivened the discussion. Once he spotted an apparently disinterested student slouching in the back of the room, and, before posing a question to him, announced he would dredge the back of the student’s head to see if he could extract a fact.

As a respected scholar in his field, Professor Newhall had authored, among other things, 31 volumes for classroom teaching, the Berkshire Studies in European History. But what mattered to us as young students was what transpired in the classroom. The consistently engaging level of teaching offered by Professor Newhall—including his insights and wry observations—easily crossed the decades that separated him from us. Late in his life he left his mark on history students of yet another generation at Williams.

Bob Heiss ‘68