When your life is going really well, why would you want to change it?

What have you got left to prove? Why risk destroying the upward arc of a successful career by taking on a challenging, new job in a different part of the country….or the world? Our classmates Clint Wilkins and Mike Herlihy each took that risk.

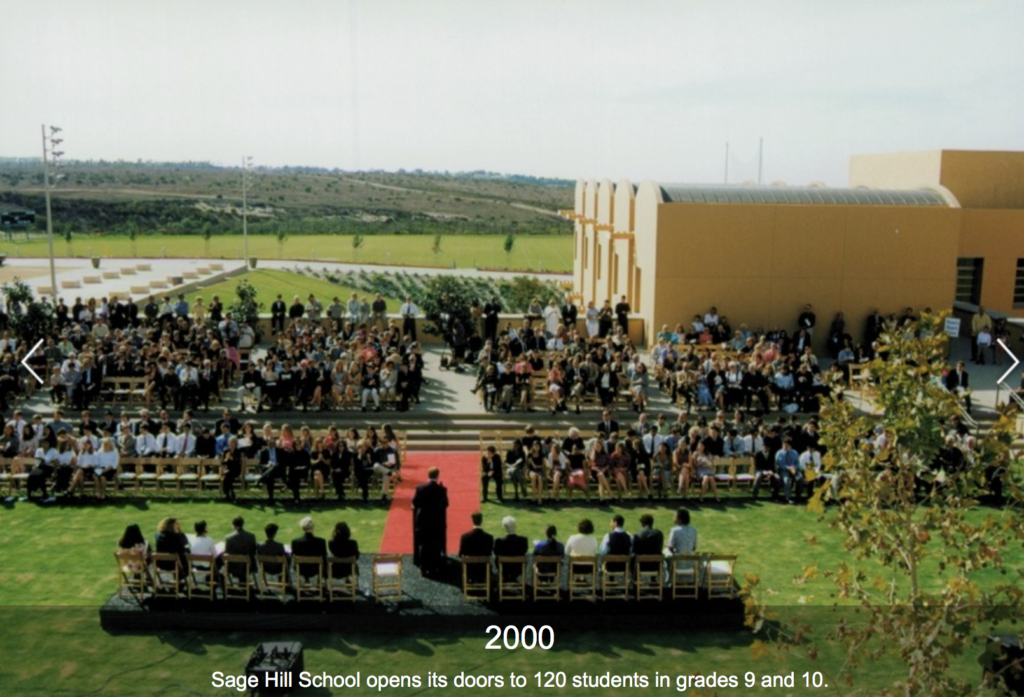

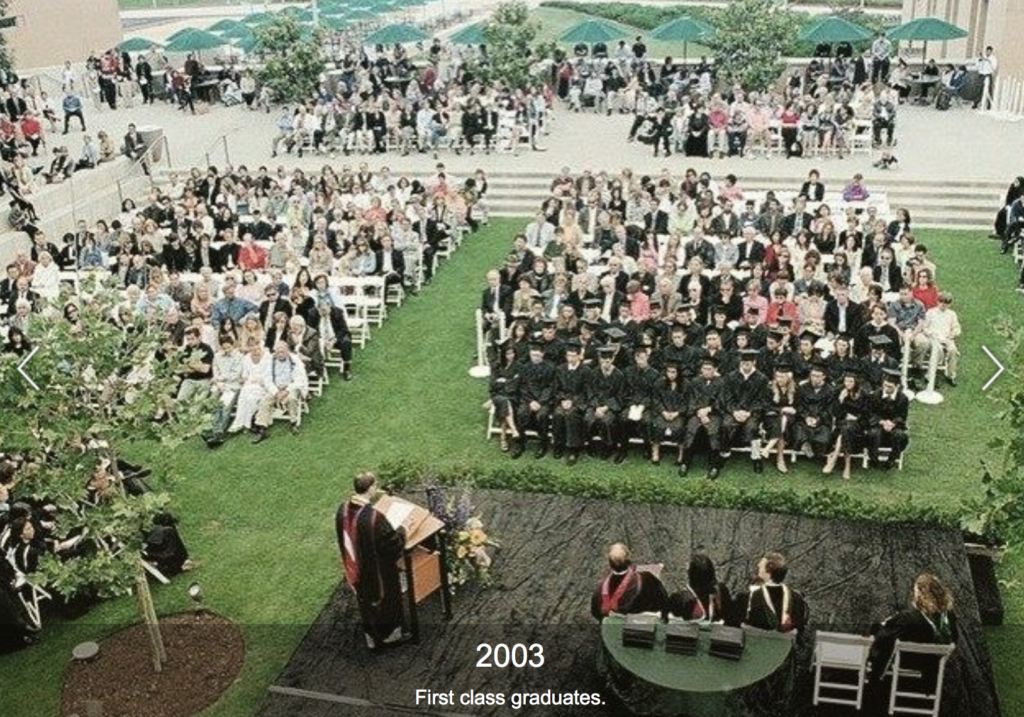

Clint Wilkins, after sailing high at the prestigious Sidwell Friends School, (with alumni such as Tricia and Julie Nixon, Chelsea Clinton, Malia and Sasha Obama) in Washington DC (1975-1987), had a few exciting career adventures running private schools in Baltimore and Oakland before he was coaxed out to California to help start an elite, superbly well-funded private school in Orange County, California. After nearly ten years at the top of Sage Hill School (1998-2006), he departed and took a year off “from the adrenaline rush,” and within eight months found himself “parachuting in” to help CiviCorps Elementary (2007-2009), a struggling inner-city, charter school in Oakland, where funding was $6000 per student, instead of the $40,000 per student at Sage Hill. Despite Clint’s hard work, the charter school was closed in 2012, three years after he left.

Seeking a totally new and different challenge after a successful career at State Street Bank, in Boston, Mike Herlihy quietly and effectively began helping struggling schools, first at Nativity Preparatory School, in New Bedford, Massachusetts and then at Byimana School of Sciences, in Rwanda. While in Rwanda, Mike also helped young Rwandans from the financial sectors make connections with Williams’ Center for Development Economics. Mike reports than nine or ten of them have gone on to earn Master’s degrees before returning to Rwanda. Mike notes that moving from his comfort area in sales into a new world for him of education, tested his willingness to try something really new.

We think Clint’s and Mike’s stories illustrate not just how career changes or transitions can be positive, but how the ability to make these changes can be influenced by education, combined with individual temperament and character. Clint believes his lacrosse and hockey activities at Williams taught him the true value of teamwork and how to work with the sometimes cumbersome duties of a committee. He believes the example of his lacrosse teammate Peter Miller inspired him to get involved with social justice issues later in his life. Mike credits David Park, his physics professor at Williams, with encouraging him never to be afraid of trying something radically new. Perhaps you will see your own career decisions reflected in their journeys. Both Clint and Mike took risks, endured failures, and received rewards. Fifty years after graduating from Williams, all of us know the challenges and opportunities we have navigated. We present this interview with Clint and Mike as two examples of the adventures we’ve all hopefully enjoyed. They provide inspiration for us all to move forward. There is still stuff to be done. Don’t sit on your laurels, but see possibility.

Moderator Lloyd Thomas (a 35-year veteran of community college teaching), asked Mike and Clint to describe what inspired them to take on these challenging educational projects.

Mike: “It was really a kind of an operational, administrative, developmental challenge.” (describing his involvement helping Nativity Prep School in New Bedford, Massachusetts)

Mike: “It was really a kind of an operational, administrative, developmental challenge.” (describing his involvement helping Nativity Prep School in New Bedford, Massachusetts)

Lloyd: What inspired you to get involved with helping struggling schools like Nativity Prep?

Mike: It’s going to sound a little funny, but fear. I left State Street Bank. I wasn’t planning on leaving. They didn’t ask me to leave. But they offered me a lot of money. When I finally analyzed it, and counted it out, I figured I’d be working for another ten years for them and not really be much further ahead of the game. So, I left, but I didn’t know what I was going to do with myself. And I’m not much fun to be around when I don’t have direction and purpose.

So fear was the main reason I started poking around. I wanted to get out of the country. Maybe go to China or Africa. I went to meet this guy who was running this school down in New Bedford, Massachusetts, called Nativity Prep. And he said, “Yeah I can get you to Africa, but I really need some help here. Could you help me out.” And I was kind of caught by surprise, so I said, “Well I don’t even know how to spell ‘education.’ I don’t know how I could help you. I’m a sales guy.” He said, “Oh you can help. I’ll give you a day a week to come in and help us.” And four months later, I was chairman of the board, trying to bail this place out. Nativity Prep was an independent middle school. Jesuit model school. 60 kids. For instructors, we had Teach for America type students just off the college campus. So it was small. We had a faculty of 7-8. It was a great idea. It was just in trouble financially. It didn’t have a real support system around it. We spent 7 years putting a support system around it. It was really fascinating. Since then most of what I’ve been doing is education oriented.

Lloyd:The lessons you learned in New Bedford, you later went over and used in Rwanda, right? You had developed the perfect template: sponsoring students, helping faculty, creating jobs.

Mike: We did apply some of it, yeah. The student sponsorship piece was part of the model we used in New Bedford. We certainly got computers into the schools in New Bedford. It was really a kind of an operational, administrative, developmental challenge in New Bedford. Most of the people who could really do something for the students were the teachers who came off the college campus or the mentors we found for them. Outside resources that we brought to bear. Things of that nature.

The “Decade Long Adrenaline Rush” — Clint on Creating The Sage Hill School in Orange County, California

Lloyd: Now Clint, you’ve heard a little bit of Mike’s story before. Is there anything you’d like to follow up on?

Clint: What comes to mind immediately are points of contrast and comparison in terms of what inspired me. I was at a slightly different phase of my career. I felt that I had another good run in me. Unlike Mike, it wasn’t that I was leaving my profession or my training to go into a different context. I was approached by a group of “investors” in Orange County. And while Mike saw that there wasn’t much of a support system in the New Bedford school he went to, we had support galore, at Sage Hill, at least in terms of money, contacts in the community, influence. All the resources were there, they just needed to have been mobilized and put into action.

So there are some real contrasts. Mike was at a school for low income kids, first generation striving to go to college. In contrast, I was recruited to run what the press always termed a “prestigious, tony, elite independent school.”

So there are some real contrasts. Mike was at a school for low income kids, first generation striving to go to college. In contrast, I was recruited to run what the press always termed a “prestigious, tony, elite independent school.”

They are very different animals. So there are lots of interesting and different contrasts between Mike’s experience and mine. I was inspired by the lure of adventure. I constantly complained in my career that I was at these wonderful independent schools like Sidwell Friends and College Prep in Oakland — that I was kind of punching kid’s tickets because they were already on the path to success. The difference I seemed to make was between their going to go Yale versus Bates. Big deal. So, big whoopee!

So, I really always had had the urge to do something new and different. For example, I took a sabbatical in mid -career to work at Stanford as a visiting practitioner studying charter schools. So, if you only get one go around in this world, why not jump off and take some risks and start something new? And while Sage Hill was not that different from a lot of the schools I had helped run, at least it was an adventure and a decade-long adrenaline rush. And for good measure I had promised my kids that we would get back to California.

There were other points of contrast with Mike’s experience. Out in Orange County, California, we were in a county that’s pretty wealthy. That may be a contrast to the New Bedford area. We had high tech and all kinds of development going on. Whereas, I think New Bedford may have, until recently, seen its better days. So all of those are contrasts and comparisons. So I just had that itch to start something fresh and new. As one of my friends told me, as I was leaving to drive across the country, he said, “Just think. All your neuroses will be institutionalized.”

Lloyd: Clint, you remarked about feeling that you were just “punching the ticket” of students who were already on the glide path to success. Did you try to put a different spin on your new school?

Clint: Certainly, Sage Hill is modeled from and is an amalgam of my experiences and some of the Board member’s experiences. The original mission of the school was to be “bold and daring.” Like no other school on the planet.

They had been looking for people outside the box and when the consultant called me she said that the board members were now looking “within the box.” Sage Hill is not a Quaker school, but it’s got a lot of Quaker values in it. A number of the Trustees wanted something different from anything else that’s ever been created—while others just wanted to get their kids into Stanford or Columbia. It’s a reflection of its community, but still, it’s a pretty special place.

It was designed as a progressive alternative to the stereotype of Orange County. So, people came out of the woodwork. Orange County has 3 million people. It’s the size of Connecticut. And Connecticut has 45 independent, non-denominational high schools. And Orange County was just looking for something similar but superior to what Connecticut had.

So when I described the support system. There was a lot of money. It was at the end of a high tech bubble in 1998. There was a lot of money from the real estate development entrepreneurs and to a lesser extent, from the tech sector. We raised a lot of money. Almost $30 plus million. So, all the potential was there, but it needed to be mobilized and put together.

Lloyd: Does Sage Hill have anything to do with the Sage Hall dorm at Williams?

Clint: No. I think Sage Hall at Williams is tied to what is now the Russell Sage Foundation; but I don’t know for sure. Sage Hill School got its name because it was located on a hill and there was sage on it. And there’s a double entendre because sage means “wise and thoughtful.”

“We kept the class size small because we were asking first year college students to teach them”–Mike on Training Teachers at Nativity Prep in New Bedford

Lloyd: Mike, tell us a little more about your first experience helping schools.

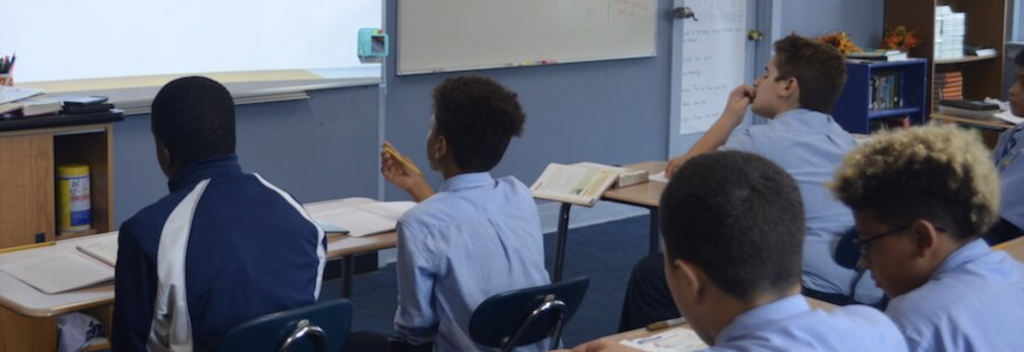

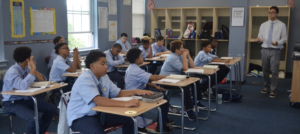

Mike: The first school I helped was the Nativity Preparatory School for Boys. This was about the tenth school of that nature that was launched by the Jesuits. We took fifth graders out of the New Bedford School System for the most part and some of the neighboring towns. Usually kids that had some ability to perform but who weren’t really performing all that well. Coming from families that were often a single parent or just a guardian. We only had fifteen in a classroom. [39:10 – 39:48] We kept the class size small because we were asking first year college students to teach them, and we didn’t want to give them a classroom management problem that they couldn’t handle. And our students graduated from eighth grade four years later. I guess they would come in performing at maybe a third grade level and leave performing at about an eleventh grade level. Pretty impressive stuff. But probably more importantly they were motivated, and they had acquired some learning skills that they wouldn’t get from their own environment.

Mike: The first school I helped was the Nativity Preparatory School for Boys. This was about the tenth school of that nature that was launched by the Jesuits. We took fifth graders out of the New Bedford School System for the most part and some of the neighboring towns. Usually kids that had some ability to perform but who weren’t really performing all that well. Coming from families that were often a single parent or just a guardian. We only had fifteen in a classroom. [39:10 – 39:48] We kept the class size small because we were asking first year college students to teach them, and we didn’t want to give them a classroom management problem that they couldn’t handle. And our students graduated from eighth grade four years later. I guess they would come in performing at maybe a third grade level and leave performing at about an eleventh grade level. Pretty impressive stuff. But probably more importantly they were motivated, and they had acquired some learning skills that they wouldn’t get from their own environment.

We’d do things to try and get them acclimated. Teach them to play chess. Get them a tennis racket and a blazer. The scale of what I was doing compared to what Clint was doing …..we were on different planets. They are both important. They are both making huge contributions.

Clint: At Nativity school, the kids would go from second or third grade level to ninth to eleventh grade level. That’s a huge accomplishment and more central to the mission of an educator.

Lloyd: Mike, how did you get these college volunteers to come to Nativity Prep and work with these small classes of disadvantaged students?

Mike: Well, we recruited first from the Boston Colleges, Holy Crosses, Notre Dame’s, but then it spread out. Then, we started using the teachers who were there as our recruiters. We got Board members to throw in frequent flyer miles. We’d fly our teachers to Pittsburgh and Penn State, and pretty soon we had a more representative group of young people as teachers helping us out.

Lloyd: By the time you were working in Rwanda, you had developed a strong teacher training component based on active, student-centered learning. Back at Nativity Prep, was there any way you helped those young teachers develop along those lines so they weren’t just improvising all the time?

Mike: You kind of hit upon one of the main conundrums of our situation. Do you go and get really qualified teachers and add to your budget so that you can’t really afford what you’re doing? The whole budget for this thing was $384,000 for sixty kids. Not a lot of money. Or, do you say, maybe having 80 hours a week of a young, enthusiastic 22 or 23 year old is a better deal than having all the best preparation of teachers in the world. I felt that the second part was true, and we started supplementing that by finding retired teachers that wanted to come in and mentor our teachers and getting them exposure to learning opportunities to improve their skills.

Mike: You kind of hit upon one of the main conundrums of our situation. Do you go and get really qualified teachers and add to your budget so that you can’t really afford what you’re doing? The whole budget for this thing was $384,000 for sixty kids. Not a lot of money. Or, do you say, maybe having 80 hours a week of a young, enthusiastic 22 or 23 year old is a better deal than having all the best preparation of teachers in the world. I felt that the second part was true, and we started supplementing that by finding retired teachers that wanted to come in and mentor our teachers and getting them exposure to learning opportunities to improve their skills.

And we ended up not only graduating students into the ninth grade into secondary school, but we graduated some of these teachers into educational careers. We ended up raising money ad hoc to get a young lady a Master’s degree at Boston College. Now she’s teaching quite successfully. She has parents who were educators. So, it became a multi-faceted thing, and I think one of the things that is in common with what Clint did is that all these things are about building a community of interest around them. And reinforcing it. Whether they have no money or a lot of money. You have to have the right mixture of treasure, time, and talent.

“We wouldn’t be hiring any rookie teachers.”—Clint on Hiring the Best Teachers and Administrators at Sage Hill School

Clint: I made a pact with the Board that we wouldn’t be hiring any rookie teachers. After all, we were new, and there were a lot of people who were skeptical about us. So, I was pledged to find experienced teachers. We had to pay them accordingly. We made sure that our teachers were paid in the top echelons in the independent school world. This was critical to meet our number one goal and priority: to find the most talented teachers possible. I had three “simple” criteria for the teachers and staff we recruited: to be really knowledgeable of their academic discipline, to enjoy the good company of teenagers and to be good colleagues. I’m sure Mike was looking for very similar, but we were paying for experienced people. And we put for the top of our budget to pay our teachers in the top tenth percentile of the recommendations of the National Association of Independent Schools. So that was a major difference.

A similarity with Mike is that we hired administrators whether it was for the Admissions Director or the Assistant as what I call almost franchise players, in other words, young educators, 28 or 30 years old, who were going eventually to go on to be heads of schools or leaders, but we swooped in and hired them maybe two years before they’d normally get that promotion if they had stayed at their current school.

Number one priority for both of us is finding the absolutely best teachers possible and supporting them.

Lloyd: I see what you mean about having administrators whom you knew would eventually advance but giving them a chance to jump up in their career more rapidly than if they stayed where they were. What kind of staff development did you have for your superb teachers after you hired them for Sage Hill?

Clint: We had a pretty big budget. But, we didn’t invest as much in their own individual professional development as much as we did later on. At first there was just so much to do “close to home” — in terms of building the curriculum, building the team, etc… So, it was kind of a juggling act. It was such a heady experience for them to actually start a school and create their own curriculum within the California curriculum requirements.

We also brought in experts in curriculum who could support teachers, who were in effect writing our own curriculum, discipline by discipline. We also sent our teachers off all over the country to help with getting the word out to colleges, such as University of Chicago or Northwestern. We fanned out to New England, the East Coast, the South as right in our own back yard— and in short order, the world of higher education had heard about this terrific new school. The Board and I wanted it to be a school that had a national reputation.

Lloyd: How many people did you have helping you? Did you have all the headaches? You must have had a good team to work with.

Clint: At first it was I and fourteen board members in an office building across from John Wayne Airport. The first person I hired at the beginning of the second year was the COO whom I hired away from Sidwell Friends. Then we hired a Dean of Studies. Then an Admissions Director. So, by then, we had a full Administrative team in place. The Academic Dean was in charge of faculty hiring, and I had my hand in it, too. The Director of Admissions did all the admissions work. We all worked together, since we had enough of a staff in the second year to pull this thing off.

The first year we had 120 students. We had 90 freshmen and 30 sophomores. The second year we had 260 students. And today, the enrollment is around 500.

“I have hundreds of kids from the country that can’t afford to be here. They are smart. And they deserve a chance in life. Can you help with that?” — The Request that Started Mike’s Work with The Byimana School of Sciences in Rwanda

Lloyd: Mike, when did you make the switch from New Bedford, Massachusetts to Rwanda, Africa? How did one lead to the other?

Mike: The headmaster that I went down to see was working with a nun to start a girl’s school in Africa. I worked with him for the first year in New Bedford, and then I went over with him to help start this girl’s school. It turned out that there were a lot of women interested in the project. Educating women in Africa. And I didn’t quite fit in. So I went over to this other school that was already existing…. 800 girls and boys. From grades 7 through 12. And that’s where initially I got introduced and eventually I brought my wife Penny over about seven months later. We’ve been working there now about fifteen years. This is the Byimana School. In their local language, it means “From God.”

Lloyd: What was different about working at Byimana in Rwanda compared to Nativity Prep in New Bedford?

Mike: Well, it had an existing structure and a need for help. We got some very good advice from a Jesuit priest we met with before we got into this stuff. He said, if you want to feel really good about what you are doing in Africa, find someone who is really doing something important and could use some help and give them the help that they want and ask for. So, we found this headmaster over there, Brother Stratton and we asked, “What do you need?”

He said, I have hundreds of kids from the country that can’t afford to be here. They are smart. And they deserve a chance in life. Can you help with that?

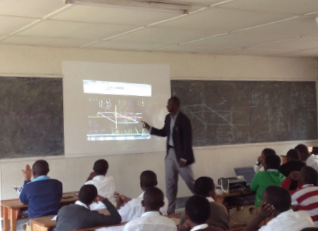

So we started building programs to get these kids through school. We had a little more gas in the tank. Then came the question, how could we help with the quality of what was going on in the classroom. My wife Penny and I both had backgrounds in computers, so we developed a program of empowering teachers, which in their language would be called “eMwalimu.” “eMwalimu” is a very respected honorific for a teacher over there. The first President of Tanzania would rather be called “eMwalimu” than President, because it means more. So, we put projectors in the classrooms, but we couldn’t afford whiteboards so we used 50 cents worth of paint in the middle of a blackboard. We kind of bootstrapped our way into it. We found a great digital library, because the Internet was not reliable. There was a guy out in Los Angeles, Jeremy Schwartz, who has put together 3000 videos and textbooks from K through 12, the Great Books, health guides. It’s called RACHEL – Remote Area Community Hotspot for Education and Learning. So we used that as a base for the teachers to start to use these tools in the classroom. And they were pretty adept at it. That was about five years ago.

Lloyd: So it wasn’t constant online streaming, but it was a resource you could get access to?

Mike: You could take broadband video classes like you do in Orange County, but without the Internet.

Over fifteen years, we’ve raised over $350,000 which is not much compared to Clint’s $30 million challenge at Sage Hill. It’s just a completely different scope But it’s helped. Rwanda is one of the few places in Africa which has universal education. The kids aren’t running around in the streets. They’re in school.

Clint on Leaving Sage Hill and “Parachuting into” Civicorps Elementary School in Oakland, California.

Clint: I don’t want to bore you with details, but over the span of twelve years at Sidwell Friends, I first started teaching four sections of US History. Then I became Dean of Students. Then College Counselor. Then Principal of the High School. Then Assistant Headmaster. I did almost everything including starting a Lacrosse program.

Once I moved out of the classroom, I always felt the weight of the responsibility for the entire community, with all its constituencies and complexities. It’s a different skill set from teaching. But all rooted in the growth and development of kids. They need to be responsible citizens.

If I could just mention what I did after Sage Hill, which kind of parallels Mike’s course. Mike went from Nativity Prep to Biymana in Rwanda. And Biymana probably had fewer resources than New Bedford. I went from Newport Beach to Oakland. I promised my family we wouldn’t grow too old in Orange County.

So we moved up to the Bay area and I got a call from someone running a charter school who needed help.

So, less than a year after I’d left Sage Hill, in early February, they parachuted me into this school called CiviCorps Elementary that needed help. And while Sage Hill needed $40,000 per student, at this charter school, we received about $6000 per student to educate them and to run a school for really needy kids. They were Title I kids. 84% were below the poverty line.And every day I just woke up to the fact that the resources that went to my Sage Hill kids was 5 or 6 times greater than at the new, struggling charter school where I was trying to help. Some of these kids were born as “crack babies.” There were these insoluble issues. Every day as I opened the car doors of the kids as they were coming in to the elementary school, I would just think about how did we get put on the planet. We didn’t have any choice. We are all accidents of birth. So these inequities and inequalities just struck me in terms of resources and in terms of creating a base for these kids to be successful.

So, I got a taste of Mike’s world, but with one major difference: In Oakland, with the best of intentions our school seemed to be doing too much — a program too many options and initiatives — so much so that the faculty and staff were getting worn out. We needed to focus more on the basics.

So both Mike and I were working with really needy kids. Low income kids. In environments that were under-resourced. That was my last full time gig in schools.

Clint: I’d always felt a moral imperative to try and use my skills for those who didn’t get a really good start in life.

“If you can’t find a job, make a job.”—Mike on Creating Jobs and Careers for Byimana Graduates

Lloyd: Mike, your work in Rwanda also resulted in the development of a job creation component.

Mike: We got to be 5 or 6 years into this. They’d struggle in university, because we didn’t help them after they graduated from Byimana high school, because we wanted to focus on the other kids were just coming up. And so they’d make it through university and then there wouldn’t be work for them. The country has not developed enough for them to need professionals. So they’d be really stymied. What can you do?

We talked to the people at Babson College, a local Boston area college, which we did. And they said, if you can’t find a job, make a job. From a neighbor, we got an introduction and got to know Dennis Hanno, the Dean of Students there. One time, I think it was Christmas time in 2010, in our living room, we all cooked up this scheme to run an entrepreneur academy in the summers. Dennis brought a dozen students, teachers and staff, to our school in Rwanda.

At first, Brother Stratton organized 80 or 100 high school juniors from across the country, together with some of their teachers. In six days Dennis and his team taught them how to develop a plan to start a business. That was electric!! You’d take these kids through the program, and then all of a sudden, they could see the way out of Dodge. Their communication skills would ratchet up an order of magnitude.

Buy my tomatoes! It was really something. That was eight years ago. We will have our ninth meeting and we’ll probably put our 1200th student through that program this summer. And we’ve found other NGOs to help. We’ve had two of our Entrepreneur Academy students graduate from Harvard last year. One from Babson.

But that’s impressive but not that important. What about the other 1100 kids who didn’t get out of the country? They are seeing a way to push forward in life. We can really make a difference. On Sunday, April 7, Rwanda will be marking its 25th year since the terrible genocide.

So, more than a couple Byimana students finished their studies and went to the United States. Out of the 600 we helped through high school, I would say there’s got to be several dozen that have gotten over here. Some have gone to Oklahoma Christian. Others have gone to MIT.

Looking at the last two chapters that Clint talked about how he put together a stellar, vibrant, first class, large scale secondary school in Orange County, And then in Oakland, California, at Civicorps Elementary School, he came up and started helping people who didn’t know what they were going to do about getting their kids educated. At Nativity Prep, we found it was easy to raise money if you said, Wow, we’re going to get them into Deerfield Academy, but that wasn’t so good for all the kids. Out of the 15 or so kids we’d graduate in a year, maybe one or two could matriculate through that kind of a school successfully and not feel like they were all by themselves. 40-60% of the students should be going to the local vocational school, which happens to be excellent in New Bedford.

“I Didn’t Pay $200K for my daughter to go to the University of Michigan!” — Clint on Parental Pressure in Elite Schools

Lloyd: I want to give Clint a chance to talk about pressure from parents at this elite school he helped start.

Clint: Let’s go back toward the beginning of my career first. In every school I was in the pressure was considerable. I was a college counselor for one year. I can’t tell you how many sessions I had where the parents and the kids came together. The parents would say really nice things, like I really don’t care where my child goes as long as he or she is challenged appropriately. But the kids took that to mean, Yeah, I don’t really believe that. There’s immense pressure on me.

Fast forward to today: I just read something about how parents today are putting down other parent’s kids to prop their own kids up for the college hunt. It’s nuts! For the so-called “elite,” there is this false belief that there are only 50 colleges that have the status that these wealthy, influential, accomplished parents want for their kids. It’s kind of a combination of things. I’ll tell you just one quick story.

During one of my years, I can remember in early May a woman, whom I thought I knew pretty well, stormed into my office and said something to the effect that “I did not send my daughter here for the last twelve years and spend (she named the figure, almost $200,000) for my daughter to go to the University of Michigan. She slammed the door and walked out. Her daughter had gotten into the Honors Program at the University of Michigan. Anyway, she actually verbalized what no one else wanted to admit. Getting admitted to a recognized “top” college or university drove everything. Fortunately at the Quaker schools I was at, we had this competing set of values that could put things into some perspective. Anyway, I could go on and on. The pressure was intense, and it was the bottom line, and it was the prestige of the family, the kid, the identity of the kid—it was all rolled up into one nasty ball.

“Now in our Rwanda program, we have our ninth or tenth master’s matriculant from Williams’ CDE”—The Influence of Williams on Mike’s Career Decisions

Lloyd: When you were involved in these educational endeavors, did you think back to your Williams experience, and if so, what made a difference to you?

Lloyd: When you were involved in these educational endeavors, did you think back to your Williams experience, and if so, what made a difference to you?

Mike: You know, I didn’t realize what was happening to me at Williams, and I don’t know if Williams realized much about me while I was there either. I kind of looked at the college experience as a kind of adventure. I was a capable student, but I was not a very academically motivated student. But I tried a whole bunch of things. In Professor David Park’s physics class, he handed me Schrödinger’s Wave Equation books and said, “Oh, by the way, it’s in German.” I had had a year of German. So I said, “I’ll try it.” And I have been a little bit irreverent about my own capabilities. So that experience translating German probably gave me a good grounding at Williams. So, I’ve made it this far. It’s fifty years later. And things worked out. That’s one perspective. And I think I got a liberal education. As I said, I tried a whole bunch of things. African history. Like a lot of our classmates.

The other thing that was interesting happened about ten or twelve years ago. A Williams College trustee and I were playing golf, and he’d heard about some of the things we were just starting to do in Africa, like giving kids sponsorships to go to school. And he said, “Have you involved Williams?”

And I said, “I did talk to Phil Smith a little bit about it, because he’s done some travel, trying to balance out the classes at Williams.” And the trustee said, “Well, shame on you. You should get going on this. Do you know “Cappy” (Catherine) Hill and Tom Powers? You’ve got to go meet Cappy Hill, who was the chair of the Williams Center for Development Economics.” (Catherine Hill later became Provost of Williams, and then President of Vassar College. Tom Powers has led Williams’ CDE through today). That was about 2008 or 2009, and now in our Rwanda program, we have our ninth or tenth Master’s matriculant from the Williams CDE now. And a couple of weeks ago we took the former headmaster and the new headmaster from the school in Africa out to Williams. Clint’s sister Wendy Hopkins, who was Secretary of the Williams College Alumni Society, told them how to start an alumni program and reach out to women in the student body. Brooks Foehl added his advice. They met with Don Kjelleren and developed some internships at Byimana for Williams students to apply for grants enabled by the Class of ’68’s Center for Career Exploration. Also, Williams Professor of Physics Tiku Majumder took us through his laboratory. It was just really magnificent. Showing how students get involved and want to stay and do real research in the summer. And he was doing some of the same research that I was involved with back in the 60s when I did my project on Schrödinger’s Wave Equation.

“What I really learned at Williams was in knowing how to put together a group of people and how to work for a common goal”—The Influence of Williams on Clint’s Career Decisions

Clint: While I squandered my Williams education academically (I really didn’t catch fire intellectually until graduate school), I got something truly worthwhile out of it that would serve me well: I mainly played sports and I learned first-hand about teamwork and I learned to appreciate my teammates who were more talented than me. So I really didn’t look too much in the rear view mirror, but I think that by rubbing elbows and shoulders with people who were really accomplished, whether they were my roommates or classmates, or professors, it kind of just got ingrained in me, what excellence is all about.

Clint: While I squandered my Williams education academically (I really didn’t catch fire intellectually until graduate school), I got something truly worthwhile out of it that would serve me well: I mainly played sports and I learned first-hand about teamwork and I learned to appreciate my teammates who were more talented than me. So I really didn’t look too much in the rear view mirror, but I think that by rubbing elbows and shoulders with people who were really accomplished, whether they were my roommates or classmates, or professors, it kind of just got ingrained in me, what excellence is all about.

So whether it’s writing a good essay or knowing how to analyze a social situation, I got a pretty good foundation. But intellectually, I didn’t take advantage of what was there at Williams. I guess the big take-away that I got from Williams was something really intangible, which was what I learned from my coaches, like Bill McCormick, and to some degree one professor, Ben Labaree, with whom I took a 1968 Winter Study course. So I kind of got launched academically at the end. But again, what I really learned at Williams was in knowing how to put together a group of people and how to work for a common goal.

I played hockey and had a bad case of tunnel vision. Here’s an important aside: I was really intrigued with Peter Miller’s journey through college, which was so different from mine. He played lacrosse for two years, I think, and then really got into social justice issues. He left the lacrosse team, and the spring of our senior year in 1968, when we were coming back from our southern lacrosse trip and watching Washington, D.C. burn on April 4, fifty plus years ago now, Peter Miller was literally located at the Washington Cathedral—meeting with Martin Luther King to arrange for him to speak at Williams. What a study in contrasts that is!!

You could get into a kind of bubble in the Purple Valley back in those days, and that’s one of the things I regret—not participating in issues of social justice and social change. Back then I was kind of concentrating on winning the Little Three title in lacrosse. But in retrospect, I learned a lot of intangibles at Williams—like teamwork. Sports really do prepare you for running an organization or serving on a committee.

Websites: