Everybody who met Jim seemed to love him right away but fathoming the depths of his spirit could take a lifetime and I can only tell you what I know so far. I first met James P.W. Thompson on a golden autumn afternoon in1964 in the freshman quad at Williams College. I had driven up from suburban New Jersey, my mother reading to me from books on the required reading list which I had largely ignored. Awaiting my assigned roommates’ appearance and wondering what all was next, I puttered anxiously around the soon to be notorious party zone, Entry B of Sage Hall.

Jim’s late arrival was infinitely cooler than mine and it gave off a first, faint aura of the gravitas that he gave to so many things he undertook. He’d driven from another world – deep in the countryside of southwestern Virginia – in a classy vintage Mercedes with his older brother, himself en route to Yale. Jim quietly entered our suite accompanied by his more talkative prep school classmate, Chester B. Goolrick, III who had requested that they room together. Jim seemed far less excited to be there than most of the entering class but he was open and friendly and laughter came easily as he let it be known that the only reason he wasn’t at Yale was due entirely to the whim of the stern headmaster at the elite Woodbury Forest School. Jim’s growling impersonation was funny: “Yale was for your brother, Thompson. It’s Williams for you!” So it began.

It had never occurred to me then that much of my learning experience would be enlarged and strongly influenced by a fellow student nor could I have imagined how lucky I later would count myself to have spent four years of college and, after that, a half-century of extraordinary experiences with Jim, his amazing family, and the fascinating place they hailed from. That afternoon marked the beginning of a life-long friendship during which, I think, the two of us used each other to dead reckon our different places in the world. I like to think, “It’s Thompson for you, Phelps.” may have crackled somewhere in the collegiate air.

Like many, I was first struck by the charm of Jim’s character – a quiet combination of school-trained good manners, melodious tenor voice, southern country accent, and youthful good looks – “Just like a Piero della Francesca angel” – as one of our art teachers would later have it. That evening he regaled us with rollicking tales of his year in England attending venerable All Hallows School and, though he would prove not the least bit athletic, his new love of rugby. Even counting that extra year, Jim was still the youngest guy in our class. Eventually I would recognize that it was partly the contradictions in Jim’s life that made him at once eccentric and powerfully attractive as a person. Not really a country boy he was certainly no city guy either. Having not yet visited the hill towns of southwest Virginia, I mistakenly envisioned his native countryside to look more like genteel Charlottesville than the rugged Appalachian enclave that Jim taught me to love in the course of countless richly instructive visits with him and his ever welcoming kin in Cedar Bluff.

In what I soon learned was a regional tradition, the long, slow, neighborly chat was an important part of life in Jim’s native Tazewell County and, like his three brothers, Jim could talk a lot. Conversation captured people instantly and his consummate ability to engage strangers was a magnet for new acquaintances about whom he would quickly detect telling attributes and assemble interesting stories. I think his prodigious memory for everything he saw or heard was part of what made Jim was so likable. Like a novelist creating characters, his vivid descriptions could verge on the hyperbolic but they deftly tagged personalities right away.

When a football appeared out of nowhere that first afternoon at Williams and a game quickly ensued among assembled strangers, I stretched a long, diving tag that apparently saved the game for our team. Nervous in my new surroundings and unsure in my every move, I was thrilled when Jim, probably wondering what other crazy, self-destructive acts I might attempt, repeatedly voiced astonishment, then and for years after at what he hailed (with no hint of exaggeration) as an athletic feat of such great beauty and extraordinary courage that it would earn a place in the vast pantheon of memorable moments he so carefully maintained. (Heroism ruled and repetition kept things accurate.) I didn’t know it then, but from that moment on, I was his.

Known to his colleagues as an original scholar, gifted teacher and educational guide adored by students, I knew Jim better as a self-installed cultural information service. An ardent collector, archivist, and critical commentator, he brilliantly leant a hip dimension to the term connoisseur.

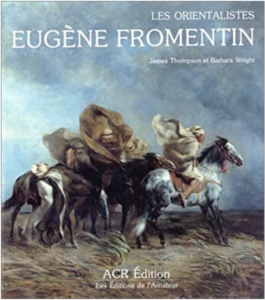

Deep fascination with French painting and iconography in pictorial art in general was overlaid by interests in literature, movies and movie stars, country music, rock and blues, baseball, beautiful women, and an intense love for the place he’d grown up (if in fact he ever did).

Deep fascination with French painting and iconography in pictorial art in general was overlaid by interests in literature, movies and movie stars, country music, rock and blues, baseball, beautiful women, and an intense love for the place he’d grown up (if in fact he ever did).

Jim was a visual person. A keen observer who used personal correspondence to clarify what he’d just observed. Despite his travels and years living abroad, he maintained for his many friends, a constant stream of post cards and two-page letters written quickly in a small, fine hand on thin, crinkly Air Mail paper. I think my usual failure to respond made him write me more often just to keep me abreast of everything I should know. As to topics, popularity didn’t count as much as excellence or distinction and selection was always based on personal preference, phenomenally derived, (as opposed to rationally or canonically). Topics were fully detailed, competitively ranked, and stored with computer-like accuracy in a vast and near perfect mental archive, ever primed for instantaneous recall. If your own memory of some fondly shared moment differed from Jim’s, you were probably wrong and would promptly learn in what way.

Jim’s dutiful career as a professor at places as different as Trinity College Dublin and Western Carolina University was devoid of self-promotion or careerist positioning. His moderate approach to academia – scholarly work without the trappings of showy academic glamour- was unusual enough to make a colleague of mine at UCLA respond to my inquiry about Jim’s unsuccessful application for a position there, “Oh, you mean the weird one.” he said. As an honors art major who drew beautifully before he came to Williams, he stunned classmates in his drawing class by refusing to work in the Bauhaus manner that Professor Lee Hirsche rigidly insisted upon. Intellectual honesty was everything to Jim when he knew it might prove politically damaging or even physically harmful as it did during the Viet Nam War when he successfully battled to be recognized as a Conscientious Objector doing it the hard way, having already been drafted into the U.S. Army. Jim’s honesty to himself could be brutal.

I always sensed that Jim was one of the most widely liked people in our college class. Everyone seemed to admire him in a warm, familial way. I’m not sure where the nickname, “Daddy Jim” came from but it arrived early and could still be heard at the 50th reunion of our Williams class which Jim, sadly, was unable to attend. For me it connotes optimism, kindness, generosity, and most of all, a fine gentleness of spirit. To some he was known simply as “Daddy”.

Barton Phelps