“For myself, although I pretend to no peculiar sensitiveness of organization or feeling, Williams College has had a strong hold on my affections ever since I left her halls, nearly half a century ago.”

– Emory Washburn, 22nd Governor of Massachusetts, Harvard Law School professor, and Williams College student in his introduction to Rev. Calvin Durfree’s History of Williams College, Boston: A. Williams and Company, 1860

Editor’s note:

There will be more coming here. A select group of ’68 historians collaborated extensively by phone and email, delved into hoary tomes and online sources to help situate the modern reader with the way it was, on and off Spring Street. We are grateful for their high level research.

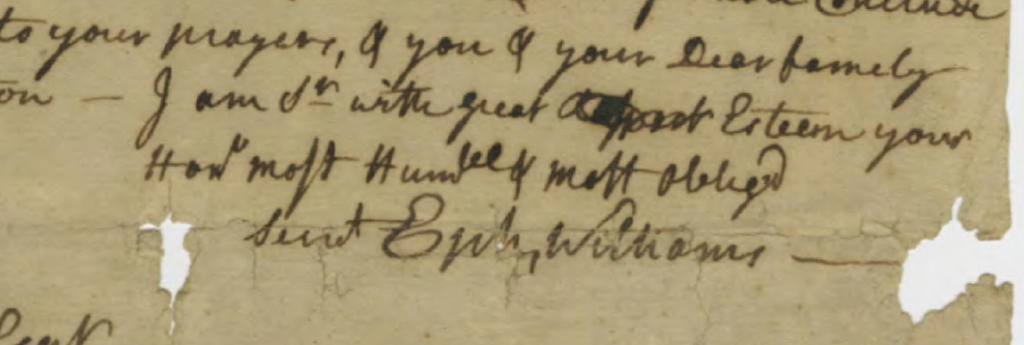

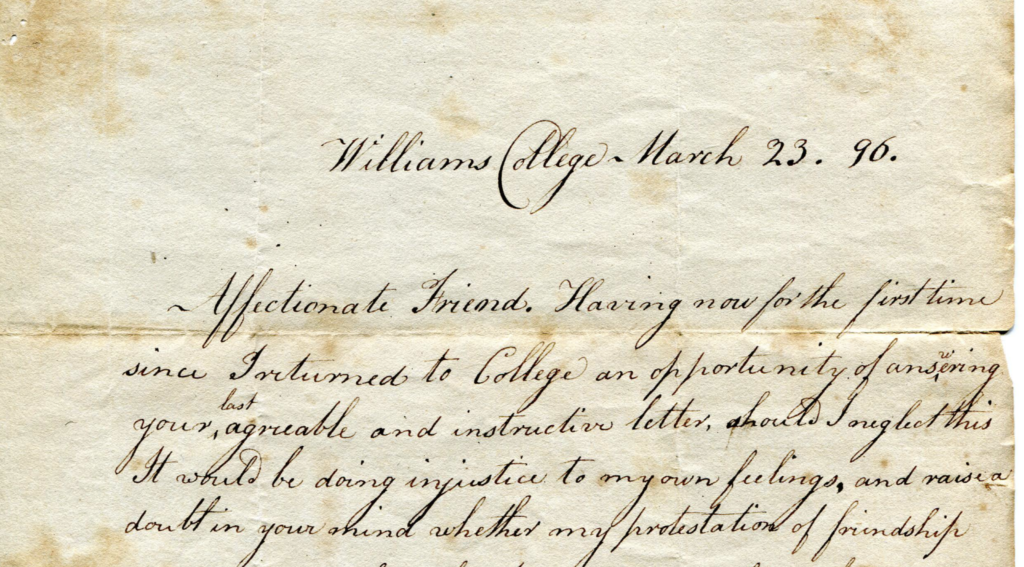

Here are some nuggets of history about Williams in the pre-modern era (Leverett Spring, A History of Williams College (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1917). Letters and pictures are from Unbound:Williams Digital Collections.

There is an intriguing story behind the protracted delay of 38 years from the death of Ephraim Williams in 1755 until the establishment of Williams College in 1793.

Eph Williams’ educational bequest (a modest $5788.07) to establish a Free School contained two conditions: the existing village of West Township must be renamed “Williamstown”, and it must remain under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts. The will did not prescribe the character of the proposed school. The two named Executors later turned out to be Tories during the Revolution.

A border feud between New York and Massachusetts over Berkshire territory that included the village, continued into the 1770s and frustrated the execution of the bequest. The New York claim was pressed by the proprietor of the Manor of Livingston. It so enraged Massachusetts settlers that they raided his iron mills and kidnapped and jailed his workers in Springfield.

The town was renamed Williamstown in 1765. Two months earlier, West Township had initially voted against a warrant to form a committee to consider Williams’ school. Three months later Williamstown dismissed the warrant again. Only in 1770 did one pass. The executors finally petitioned the Legislature in 1784, and the school Trustees were incorporated in 1785.

In 1789, the Trustees received permission from the General Court to operate a lottery to raise a sum, not to exceed 1200 pounds, for the purpose of enhancing the endowment of the planned Free School. The Free School provisionally opened in Williamstown in 1791.

The Trustees then petitioned the Legislature in 1792 for the school’s incorporation into a college to be known as “Williams Hall.” In support of their proposal they argued that the venture was already underway; it would provide an affordable liberal education to those less able to pay; it was situated in an “enclosed place” that was free from “the temptations and allurements…incident to seaport towns”; and it would also benefit the nearby states of Vermont and New York.

The charter under the name of Williams College was finally granted on June 22, 1793. This action could have been in jeopardy, since earlier, in 1763, the request for a charter for Queens College in Hatfield had been successfully opposed by the Overseers of Harvard, based on the fear that a competing college in Massachusetts might undercut Harvard. Two of the 12 Trustees of Queen’s College were executors of the Williams estate.

On October 9, 1793, the institution opened as Williams College and admitted a total of eighteen students in different classes.

In 1795 the first teacher with the rank of professor was appointed. He was a Canadian who taught French.

At the first commencement, also in 1795, four students were graduated. Each was required to speak four times during the ceremonies. Two of the student speech topics were female education and the barbarity of the slave trade.

From the beginning, and for many years, students were mostly poor, and many were the sons of farmers. One student began his college career by arriving after hiking forty miles. Another wore a coat his freshman year made of his mother’s wedding gown. Nevertheless, long before the end of the 19thcentury rumors were prevalent that it was becoming a rich man’s college.

Early student diversions included smoking, playing cards, and gambling. Hazing was called “Gamutizing Freshmen.” President Fitch shut down a class devoted to dancing that turned into a craze. Rowdy drinking followed exams. One student rebellion broke out in 1802 against March exams, and another in 1808 against two unpopular tutors. In 1806 the Pittsfield newspaper printed a letter condemning the College because “the youth there were taught to be heady, to despise government and to speak evil of dignitaries…” He thought the Legislature should intervene to stop the “baneful influences” of this notorious institution “on the morals and taste of our youth.”

In 1806 a group of students embraced the cause of foreign missions, at the Haystack Prayer Meeting, which was held just north of campus.

In 1808 a student rebellion broke out, with demands that two tutors be dismissed; they later resigned. This followed an earlier one, 1802, that had apparently centered on the March examinations.

The famed poet William Cullen Bryant entered as a sophomore in 1810 and left after seven months. He subsequently wrote, “I regretted all my life afterwards that I had not remained at Williams.” Later the Trustees restored him to the membership in his class, and he wrote a poem for the 50th reunion.

By 1815, when President Fitch resigned, the Trustees were sufficiently concerned about the viability of the institution, reflected in a substantial decline in graduates,that they considered its removal to another location in Massachusetts. This led to a lively bidding competition among other towns, including Northampton and Amherst, and, later, Greenfield. In 1820, when the College’s finances were particularly low, the people of Williamstown donated more than $18,000 to ensure its permanence in the town.

After the departure of President Moore and a professor, and the defection of fifteen undergraduates, to the Collegiate Institute at Amherst in 1821, Williams joined with Harvard and Brown to oppose the granting of a college charter to Amherst by the Legislature. This coalition succeeded in delaying action on Amherst’s petition for two years.

Amidst the turmoil relating to the defection of 1821, the Society of Alumni was formed. The first of its kind, it has served as a model that has been adopted by the rest of the collegiate world.

In 1823, eight years before the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison began publication of the “Liberator,” an anti-slavery society was formed at Williams—the first in Massachusetts.

Williams forged an alliance with the Berkshire Medical School during the years 1823-1837.

President Griffin, during a period of great religious revival in 1825, revived the fortunes of the College by raising $25,000, to be split between endowing a new Professorship and building a new chapel.

After the great revival, some students became deplorably lawless and sacrilegious, according to contemporary accounts.

While the date of establishment of the custom of Mountain Day is uncertain, it was mentioned as early as 1827.

In 1827-28 the campus saw the rise of a student temperance movement. The College responded by imposing a pledge requirement on students that they not drink intoxicating liquor or supply it to others while residing in college, but this measure gradually fell into disuse.

In 1828, the dedication of the beautifully designed building now known as Griffin Hall—intended for use as the new College Chapel—marked a turning point for the better in the College’s fortunes.

Another first for any American college was the launching of a scientific expedition to Nova Scotia in 1835, by a group consisting of three faculty members and fifteen students, for the purpose of collecting specimens. This undertaking was sponsored by the Lyceum of Natural History at Williams.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, visiting in the area, witnessed the College’s commencement exercises in 1838. He commented about the circus atmosphere created by the peddlers, hucksters and vendors of various kinds who came from the surrounding area for the occasion.

In preparation for the centenary of his death, in 1853 the alumni at their annual meeting appointed a committee to bury the remains of Ephraim Williams in the college cemetery, and also to erect a monument on the spot where he had fallen in battle in upstate New York. The monument was erected, but re-interment of the body proved impossible, after it was learned that a member of the Williams family had previously opened the grave, and was said to have carried off part of the remains.

To strengthen scholarship, in the 1855-56 academic year sophomores began to be administered four-hour comprehensive written examinations. They were followed by a “Jubilee Supper,” which featured appropriate original songs. The biennial exams were discontinued in 1866-67.

Williams lost to Amherst in the nation’s first intercollegiate baseball game, held in Pittsfield in 1859.

Enlistments during the Civil War took a toll on the registration of freshman. After the war, a monument was erected on the campus to the memory of the thirty war dead from Williams.

The adoption of the color purple by Williams dates from 1865. When the team was leaving for Cambridge to compete with Harvard, two young ladies visiting in town, learning that Williams had no college colors, pinned a purple ribbon on each member of the team. The ladies wished the team victory wearing the royal color purple. Harvard lost.

In 1871 the Trustees authorized a study of the possibility of coeducation at Williams. The study arrived at a negative recommendation, which was adopted.

James Garfield did not impress his peers at Williams as an orator or political comer until he transfixed his audience in a speech he delivered in 1856 condemning the caning of Charles Sumner on the floor of the Senate two days after he gave an anti-slavery speech.

At an alumni dinner in New York, Garfield, later President of the United States, said, “A pine bench with Mark Hopkins at one end of it and me at the other is a good enough college.” This was in 1872. In 1881, shortly before he was assassinated, Garfield paraphrased his earlier epigram in the following words: “A pine log with the student at one end and Doctor Hopkins at the other would be a liberal education.” Thus the more famous saying was coined, and the image of the “log” entered into the lore of Williams.

The wooden gymnasium collapsed in a gale during the Commencement of 1883.

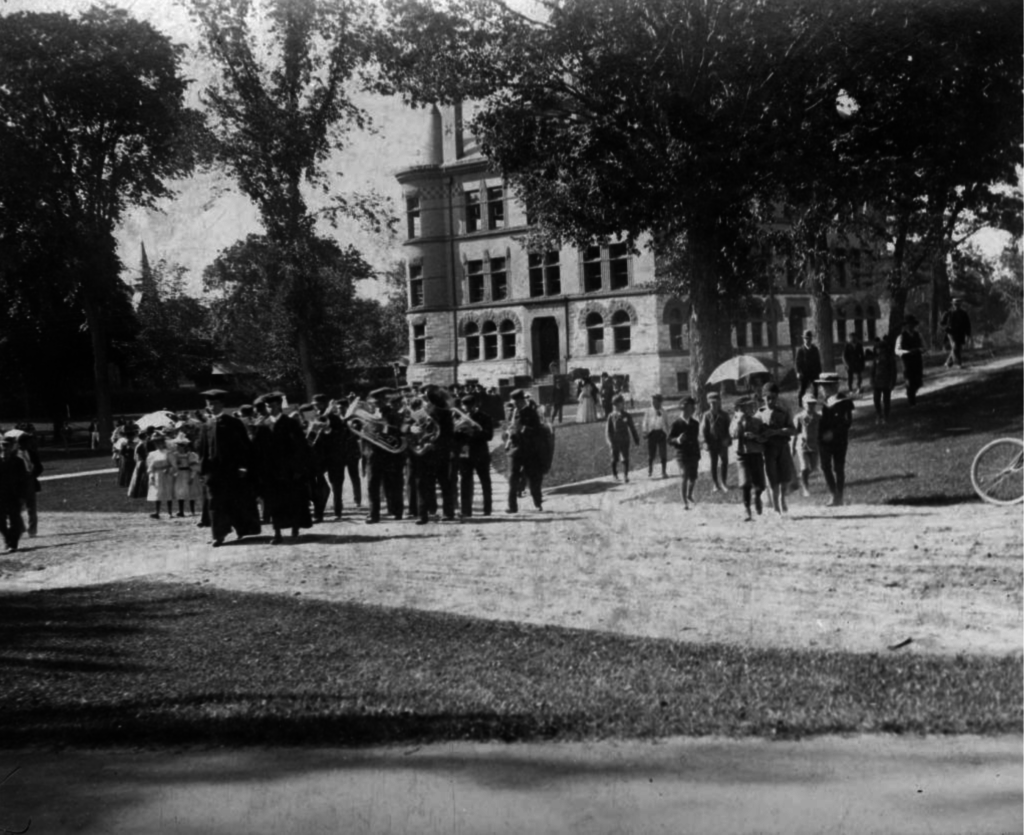

For the 1893 celebration of the centennial of the College, which Andrew Carnegie and many other notables attended, a plan was proposed but shelved to burn great beacon fires on conspicuous points of the surrounding mountains.

In 1896 the honor system was adopted for examinations.

Thanks to his fundraising efforts, President Carter by the end of his tenure in 1901 had help grow the endowment of the College to 1.1 million dollars.

In the early years of the twentieth century the College continued to enforce compulsory religious exercises, including daily prayers and two Sunday services (am and pm).

By the 1915-16 academic year, prior to the entry of the United States into World War I, the enrollment of Williams College reached 552 students.

More Williams History

- "Frivolous, conformist, and anti-intellectual"

- Class of 1850 Attends First Documented 50th Reunion at Williams

- Crossing the Border: The Williams-Bennington Experience in late 60s

- It's 1815. Let's move the Williams campus to Amherst or Northampton.

- Jack Sawyer, the Visionary President We Hardly Knew

- January 1968 and the Winter Study Program

- The Fraternity Debate -- 1868 to 1968!

- Winston Churchill, Williams College, and the color purple

Williams Today

- Ephs dominate on Pratt Field, cap perfect season

- Window on Williams - Fall 2020

- Black Lives Matter: Williamstown reacts

- Williamstown & environs in times of pandemic

- 50th Reunion of Nov 1967 football victory blessed by thrilling OT win over Amherst, 31-24

- Multiculturalism at the New Williams - The Davis Center