Editor’s Note:

January 1968 was memorable for several reasons. Without doubt, the most dramatic event was the Fort Hoosac fire, spectacularly captured in the photo by (then) Dean of Freshmen John Hyde.

But it was also the maiden voyage for the Winter Study Program (WSP), which along with our class, celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. Read below to learn how the WSP evolved, and how it changed the landscape of Williams education forever.

A brief history of the Williams Winter Study Program

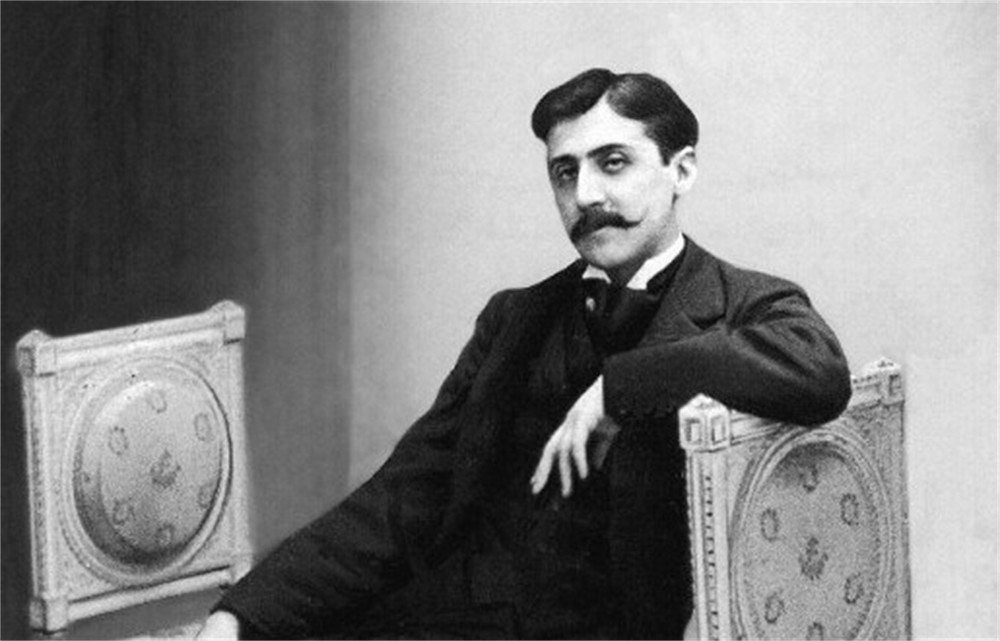

Marcel Proust, author of In Search of Lost Time, was the subject of one of the more popular course offerings of the first WSP, taught in English by Prof. John Savacool.

Our senior year was overshadowed by national political turmoil and the looming draft. At the same time the College made us guinea pigs along with everyone else for the roll-out of the first ever Winter Study period in January 1968. To do this, the academic year had been reconfigured into 4-1-4. As a result, all of us undergraduates (thankfully) were finally liberated from the syndrome of final examinations hanging over our heads during the Christmas-New Year break and awaiting us in January.

No doubt, it took a great deal of work for the Williams faculty to create the first Winter Study Program. It very nearly didn’t happen at all. While debates were going on, Smith College abandoned their month-long Interim Session in 1965, noting that “this “noble experiment… failed because of a general lack of response from the student body” (Williams Record, Feb 26 1964). On the other hand, some twenty miles north of us, Bennington College held fast to the notion, having instituted in 1932 a Winter Field and Reading Period, renaming it Non Resident Term in 1944, and finally Field Work Term in 1984.

On May 21, 1965, the Williams Record reported that the faculty narrowly defeated a proposed 4-2-4 plan, which included a six-week winter session. The vote of 51 to 43, fell below the “60 per cent majority” threshold set by President Sawyer. Undaunted by this seeming defeat, Sawyer commented that “the future is in no way closed to further consideration of related changes or alternative adaptations.”

The future arrived just one year later on May 13, 1966, when the Williams Record announced that a revised 4-1-4 program, with a 26-day winter session, was approved by the faculty. Before the vote, faculty sources had assured the Williams Record that the 4-1-4 proposal would garner at least 66 per cent of the votes. In fact, “no dissenting votes were cast.” The Williams Record editorial headline read “Hurrah for the 4-1-4.” In the Fall of 1966, departments immediately conducted meetings so they could get student input. By October 9, 1967, The Winter Study Program Committee, consisting of Francis C. Oakley, Charles T. Samuels, and H. William Oliver, Coordinator, published a list of over 100 courses to be held during the January 5-31, 1968, term.

At the end of this curriculum experiment, Dean John M. Hyde reported that only six students failed their WSP class, for work which the WSP Committee described as “perfunctory.” In a February 9, 1968 article, the Williams Record headlined, “Students Find Winter Study ‘Frustrating’ and ‘Fulfilling.’”

For Williams, this year is the 50th anniversary of a watershed change in the academic life of the College. Meanwhile, the term “experiential learning” has crept into vogue, and currently students routinely undertake projects courses in topics like Epidemiology in Public Health and Practicum in Curating: Warhol. For many of us, it was more an opportunity to take risks with a concentrated intellectual challenge, potentially in a subject outside one’s normal comfort zone. For some it has also provided an opportunity to explore a potential future career field, through an internship off campus. Still others found themselves a long way from Wiliamstown and its punishing winter temperatures.

Any classmate who participated in the anthropological research expedition to the island of Roatan, off the coast of Honduras, would argue that WSP1 was an amazing opportunity to learn and explore outside that classroom. Under the supervision of Prof. Thomas Price, seventeen students studied island ways and culture, and fulfilled their obligation to apply questionnaires, parts of which probed rather intimate aspects of island life. The Roatan 68ers have also put together their own set of memories of that experience. You can sample those here.

The Roatan project was only one of the more than 100 projects, besides the continuation of honors theses research and writing for students already engaged in those endeavors. Students enrolled in the 101-102 sequence of French, German, Spanish, or Russian, however, were required to take a sustaining program in their chosen language during this time as their project. Alternatively, a student or group of students could propose a special project to a faculty member and seek the approval of the faculty member and department to pursue the special project instead of one that was offered. Winter Study was presented on a pass-fail grading basis, and a failing grade required taking a make-up project in June—too late for us graduating seniors.

The urgent, unsettled times we were experiencing at the beginning of 1968 were reflected in the titles of some of the initial project subjects: Planning and Rebuilding Cities, The Economy of Communist China, The Literature of Social Protest in the 1930’s and 1960’s, Image of the Negro [sic], Readings in the Diplomacy of the Cold War, 1946-1963, Public Order in the Urban Community, Urban Turmoil: Race Crises in America.

Two of the more unusual WSP courses promised such activities as a trip to the since closed Yankee Atomic Power Plant in Rowe, MA (Chemistry 12) and the participatory creation of a film dealing with the theme of cruelty (Drama 11).

As part of a political science project, eight students spent three weeks in different metropolitan areas before returning to campus to write papers about their findings. For example, John Dirlam examined machine politics in Bridgeport. Williams students on globe-trotting projects also managed to fan out to Kenya, the Philippines, London, Berkeley, New Orleans, and elsewhere.

Afterwards, the internal committee report summarizing the results of the first year of Winter Study, based on a faculty-student survey, indicated those participating considered WS to be a “success” and “enjoyable.” The authors of the report, however, also found the program did not produce great “experimentation,” and it lacked “cohesiveness” in its first year. Overall, as the report noted, off-campus projects offered by faculty were quite limited, but there were some. Among the student survey respondents, the favorability ranking for the initial year of WS by class, from high to low, was the following: Junior, Freshman, Senior, Sophomore.

The inaugural Winter Study period, occurring as it did late in our collegiate careers, was certainly novel, and also a bit strange. Was it a life-changer for you? Please share with us your experiences during your one-and-only Winter Study project by submitting a comment below.

And feel free to compare the current 2018 offerings with those of our year.

Proust’s madeleine, the cookie (technically, a very small sponge cake) that started it all.