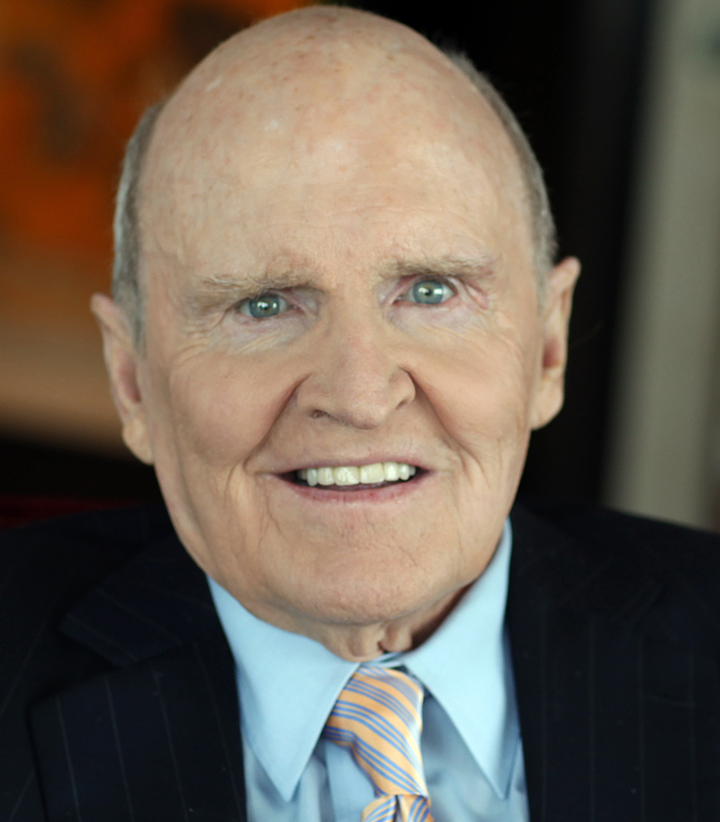

If you picked up a business newspaper or magazine in the 1980s and 1990s, superstar executive Jack Welch was the man of the hour. He served as the high profile CEO of GE from 1981 to 2001. His every word and corporate move were studied and it seemed he could do no wrong. He received the accolade “Manager of the Century” from Fortune magazine in 2000. Even a messy divorce from his second wife involving an adulterous relationship did not seriously tarnish Jack, although she collected about $180 million from him, much to the amusement of late night TV comics. With all that, on his retirement from GE, he received a severance payment of $417 million, and by 2006, his net worth was estimated at $720 million.

For a large number of Berkshire residents, “the GE”, as local residents referred to it, was more than just a job, it was a way of life, a culture, an all encompassing experience. At its height, GE employed 13,000 people in Pittsfield, The company provided good-paying jobs, funded local charities, sponsored youth sports and was a presence everywhere in the city. But by 1986, the precipitous decline of the community was well underway. Someone had decided it was over for GE in Pittsfield and the buildings Pittsfield residents had worked in and and been familiar with would for the most part remain behind as empty shells, left behind on the battleground after the war moved elsewhere.

It took a while, but looking at the city in 2022, it’s clear that Pittsfield has clawed its way back as a community and as center for enterprise. But what effect did Jack Welch have on Pittsfield and its fortunes? And how is he remembered today?

Armed with a newly minted Ph.D. in chemical engineering from the University at Urbana-Champaign in 1960, Welch began his career as a junior chemical engineer at GE in Pittsfield in 1960. This was not the Massachusetts that he grew up in, his roots were in the suburban community of Peabody, north of Boston, but Pittsfield became home for him until 1977.

He worked in the plastics facility there as a chemical engineer from 1960 to 1973. In 1968, the year we graduated from Williams, Jack was promoted to general manager of GE Plastics, a $26 million operation at the time.

By 1971 he also became the vice president of GE’s metallurgical and chemical division and in 1973 was named group executive, managing chemical metallurgical medical systems, appliance components and electronic components businesses.

Welch continued to live in Pittsfield until 1977. He once said, “GE and the community always had a very good relationship. We all liked being out there. We liked the environment of the Berkshires. We supported the city’s charities.”

In 1979 he was named the vice chairman of GE, and in 1981 GE’s youngest chairman and CEO. A meteoric rise.

During the early 1980s, in his new position, Welch became known as the master of the business technique of downsizing. He won the nickname “Neutron Jack” for the way he eliminated GE employees while leaving the building intact. He reduced the company’s basic research, and closed or sold off under-performing businesses. That is when GE’s Pittsfield operations came into his cross-hairs.

As CEO, Welch did not let the fond memory of his own Pittsfield years stand in his way. He ordered the closing of the power transformer facility. He told The Berkshire Eagle the decision was painful but “long overdue.” He claimed the facility had been losing money for 20 or 30 years, and was being carried by the rest of the company. And Welch took full responsibility for the closing, saying “the buck stops with me.” Nevertheless, he claimed “It was the last thing I wanted to do.” Transformers had been the original calling card and cash cow of the whole General Electric operation in Pittsfield. It has been described as “one of the Crown jewels of GE’s electrical infrastructure, high voltage testing and defense contracting businesses.”

At the helm, Jack Welch expanded GE into a diversified, more prosperous global enterprise; shedding less prosperous, faltering units was a tool he unsparingly used toward that end. His brutal business methods grew the company, delighted stockholders, and were the envy of the international business community. By the time of his retirement in 2001, Welch had grown GE to over $450 billion in market capitalization, of which about 40 per cent was in financial services. (Twenty years later, however, that market capitalization had dwindled to $200 million.)

For decades at GE Welch battled the Environmental Protection Agency and New York State over PCBs that the company dumped into the Hudson River at its capacitor product division plant in Hudson Falls, NY, contaminating the surrounding aquifer as well. He was a denier of the science that condemned PCBs as carcinogenic “forever chemicals”; Jack deemed the controversy merely a political matter.

At the time of his death in 2020, The Berkshire Eagle described Welch’s legacy in Pittsfield as “complex,” labeling the term as “the hugest of understatements.” The paper described his closure of the power transformer division, “the heart of GE’s presence in the city,” as the slam that “began the city’s economic slide in 1986.” It noted that during part of his tenure GE polluted the Housatonic River and properties in Pittsfield with PCBs from the transformer division. At the same time, however, his success in growing GE yielded benefits to stockholders and retirees in Pittsfield.

The Eagle recounted GE’s local charitable works as a good citizen over the years. It added, “When [Welch] became CEO in 1981, Pittsfield was confident that with a Pittsfield alum at the helm the good times would continue to roll.”

This was not to be. In an interview Welch claimed that foreign competition had made the transformer division unprofitable, but the unions disputed that. Business analysts, as reported in The New York Times at the time, were not surprised by the move because the market had been shrinking for the giant machines (30 feet long, 15 feet high and 15 feet wide), which helped build and illuminate the industrial sector. Energy conservation measures instituted in the United States in light of the Arab Oil Embargo in 1973 had the effect of reducing the demand for electricity over time, and thus the demand for transformers.

The downsizing movement Welch ran at the company devastated not only Pittsfield but also other “GE towns,”notably its original home of Schenectady, NY. Almost a century earlier, Schenectady and Pittsfield together had formed one of the hubs of the then fledgling electric industry The last vestige of GE in Pittsfield to go was GE’s Plastic Division, which was sold to SABIC in 2007 and later shuttered.

For decades GE had been the city’s largest employer, providing paychecks for two and three generations of some Pittsfield families. In its heyday in the 1940s, GE employed about 13,000 people out of a town of 50,000.

The Eagle’s opinion piece mournfully observed that all that remained of GE now were the polluting PCBs in the Housatonic River below Pittsfield. In closing, the newspaper said that “it took too many years for Pittsfield to get over its jilting by Mr. Welch but it appears to have done so.”