It was not until Winter Study in my senior year that I experienced the first stirrings of what I would later call my intellectual awakening. The scene was Ben Labaree’s home. There was a welcoming fire in the fireplace on a bitter cold January day in 1968. His son, Ben junior, would appear and re-appear, playing happily with his younger brother and his younger sister. Professor Labaree (It was unconceivable to call him anything else.) would fleetingly attend to his kids and then return to our conversation, seemingly without missing a beat.

It was not until Winter Study in my senior year that I experienced the first stirrings of what I would later call my intellectual awakening. The scene was Ben Labaree’s home. There was a welcoming fire in the fireplace on a bitter cold January day in 1968. His son, Ben junior, would appear and re-appear, playing happily with his younger brother and his younger sister. Professor Labaree (It was unconceivable to call him anything else.) would fleetingly attend to his kids and then return to our conversation, seemingly without missing a beat.

We talked some about the historical subject matter at hand (the significance of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787) and its role in the subsequent development of the American Midwest. I remember professor Labaree being especially adept in linking the past with the present. Yet, our conversation quickly turned to me—specifically how I could break out of my three-and-a-half-year-academic-funk in the limited time I had remaining at Williams. At the top of his list was to encourage me to take his course on the American Revolution in the spring semester. His reasoning: we could build naturally upon our positive Winter Study experience together.

Whatever time we did spend discussing the Northwest Ordinance that day, I remember nothing more. The scene itself, however, is etched vividly in my memory—his sons, the warm glow of the fireplace and the toys scattered about on the floor—and the skillful way he asked probing and evocative questions, especially his patience in allowing me the time to formulate, haltingly I suspect, my own responses. Most of all, I left this session in the embrace of some warm and ineffable glow. This was to become the very first moment of my intellectual awakening.

The second moment was also memorable, but this time for a very different reason. It must have been in mid-April—and the world outside the Purple Valley was unraveling. Martin Luther King, Jr. had just been assassinated and the Vietnam War was closing in on all of us. Inside the Purple Valley I was far more preoccupied with how our varsity lacrosse team would prepare for the Little Three title against Wesleyan and Amherst.

It was routine check-in, to review the status of my research on Virginia’s decision to join the other American colonies in the years leading to 1776. Much like our first session during Winter Study, I remember little, if any of the content, just that he asked penetrating questions. This time, however, the questions landed directly upon me. I found myself beginning to panic—my grip on the facts and my understanding of the larger historical context were exposed for what they were: superficial. While professor Labaree was gentle in his line of questioning, there was no escaping what had just occurred; I was grilled.

I walked out of that session with a pit in the middle of my stomach so powerful that it took days to subside. I vowed never to let this happen again! (I would later realize that intellectual awakenings, however inspirational, are routinely accompanied with more than a dose or two of pain.)

Now fast forward to the last day of classes in late May, when professor Labaree handed back my term paper, “Virginia: Its Movement for (sic) Independence.” He shook my hand and nodded approvingly as I turned to these handwritten notes: “A good, steady piece of historical work throughout. You have put together an interesting narrative of events in Virginia… While your conclusion may be a little too enthusiastic concerning the role played by Virginians in almost single-handedly bringing independence to the colonies, I can nevertheless appreciate a Yankee willing to give Virginians credit. This paper should prove to you that you are capable of doing a solid job when you become interested and enthusiastic about a topic.” B+

There was no drum roll, no grand flourish or any public recognition for that matter—no honors citation at graduation or a fellowship awaiting me at some prestigious graduate school. It was just one very personal yet indelible marker in time—the third and culminating moment of intellectual awakening in my Williams career—a few words on a 5×8 card and the formal recognition that I was, officially at this point in my own development, “solid” and “steady.”

That was sufficient—at least for the time being—all I really needed to put me on a path that would soon lead me into a career (and indeed a calling) where I, too, would become a protégé of the teacher and the mentor that Ben Labaree had so artfully modeled. And to think: these seeds were planted not over the course of a full college career but rather in just three fleeting “Mark Hopkins-and-the-log” moments as I was taking my leave.

It was Henry Adams who famously wrote, “A teacher affects eternity; he can never tell where his influence stops.” While I’m not so sure about the eternity part, I know that Ben Labaree’s influence is certainly not stopping with me, for I’ve passed along his spirit to countless students of my own. Nor has it stopped with the hundreds, perhaps thousands of other Williams students he inspired over the course of his long and distinguished career.

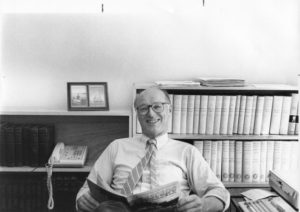

His intellectual rigor, his dedication to his academic discipline, his passion for all things nautical—this is what comes to mind when we think about Benjamin Woods Labaree, the scholar. But for me what most stands out was his gift in being able to dole out honest and direct and at times painful feedback, holding me to the highest academic standards while simultaneously communicating an unspoken confidence in my unrealized potential. This was the skill set that epitomized Benjamin Woods Labaree, the mentor-teacher.

But wait, there’s more to the story! In trying to find out where Benjamin Woods Labaree is now and how he’s spending his retirement, I googled him. That led me to Benjamin Labaree, Jr—one of the very same boys who would appear and reappear in that Winter Study session forty-nine years ago on a cold January afternoon. He, of course, is all grown up. It turns out that Ben the Younger is an accomplished historian, teacher and educator in his own right. He’s now head of the upper school at St Albans School in Washington, D.C.—just a few blocks down the street from where, coincidentally, I held a similar position at Sidwell Friends School many years before. He’s also at least the third generation in his family to become historians and educators.

So, it turns out that Ben the Elder’s influence won’t be stopping any time soon; his legacy endures, passed on not only through the lives and the careers of us, his former students, but also through an uncommonly talented gene pool. As for the affecting eternity part, I’m still not so sure, but if any teacher can pull it off, I know where to place my bet.

Clint Wilkins