To Be African-American and a Member of the Class of 1968

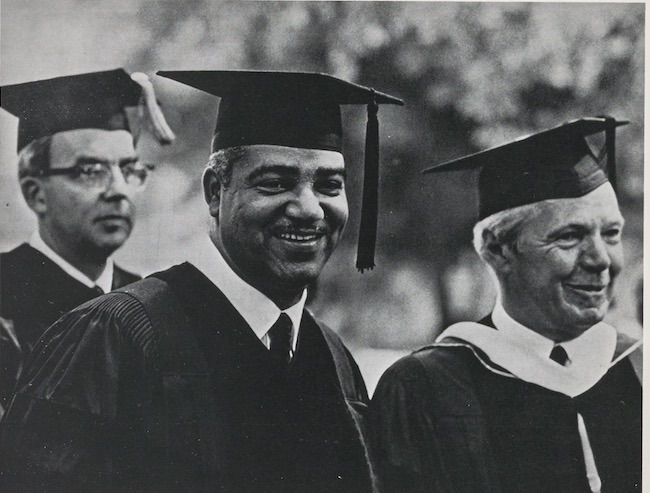

Whitney Young (with President Sawyer and NY Times’s James Reston at the 1968 Williams Graduation Ceremony

Some of the experiences of the African-American members of our class were chronicled in the Williams College Black Student Union (BSU) in 2002-2003 in Black Williams: A Written History. Members of the BSU wrote it during the 2002-2003 academic year under the guidance of Professor Tess Chakalakal. Not only was there a need for a record of the rich history of the BSU, she said, but also of the blacks who attended Williams: a written, accessible history of Williams’ illustrious black graduates would not only inform current students but would attract prospective students —especially black students—to Williams.

In order to tackle this project, the BSU board proposed a Winter Study 099 titled “Black Williams: A Written History.” With the exception of its two freshman members, the entire BSU board participated in the project. Six general members of the Union also participated in the work.

Below is an excerpt directly relevant to our class members from the Davis Center sponsored paper, which available in its entirety here. (Not familiar with the Davis Center at Williams? Click here to bring yourself up to date)

Williams remained an institution for white males until the fall of 1885, when Gaius Charles Bolin of Poughkeepsie, New York entered the college. He shared living quarters with his brother, Livingsworth Wilson Bolin, who entered Williams a year later. His acceptance into almost every facet of life at Williams proves that, by all accounts, his experience was both exceptional and enjoyable.

After graduation, Bolin spent some time working in his father’s produce business in Poughkeepsie. He also studied law with a local attorney, Fred E. Ackerman, and after two years he passed the Dutchess County bar exam on his first try. He was named head of the Dutchess County Bar Association in 1945, a position he held until his death a year later.

Fast forward to our era in the history of Williams:

College campuses are not immune to the issues unfolding outside their walls. The integration of black students into predominantly white institutions forced schools across the nation to adjust to the needs of the growing minority or face on-campus unrest until changes were made. Black students at Williams refused to let their geographic isolation inure them to the historical changes taking place in the greater society. Instead, students of the classes of 1967-1970 sparked revolutions at Williams that changed the college forever.

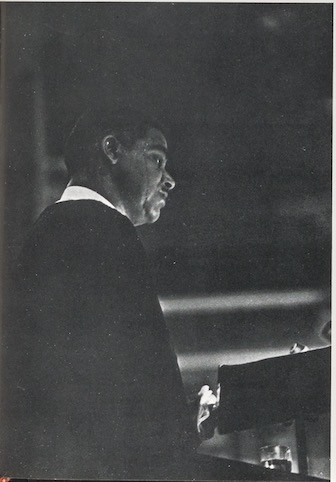

Whitney Young speaks at the 1968 Baccalaureate Ceremony (click on image to learn more about Whitney Young)

The Class of 1967 entered Williams at the beginning of a series of tragic events that would shape the 1960s. Three months into their first semester, on 22 November 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. To add to the air of political uncertainty, the country struggled in the summer of 1964 with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which dramatically widened the conflict in Vietnam. Despite these grim circumstances, black students at Williams found an emerging leader in Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose inspiring message of nonviolence gave hope to students across the nation as they grappled with the problems of a troubled world.

John H. Gladney, Jr. ’67 was one of many students who took King’s message to heart. He was instrumental in organizing a four-day trip to Morehouse College, a predominantly black, all-male institution in Atlanta, Georgia. Four black men from Williams made the long trip to hear King speak on the role college students could play in combating racism, and to learn how to effect change on their campuses using his methods of passive resistance.

The Class of 1967 boasted only four African American students— Gladney, David E. Jackson, Clarence S. Wilson, Jr., and Don Jackson. Jackson did not graduate from Williams, but he contributed a great deal to Williams by founding the Williams Afro-American Society (WAAS).

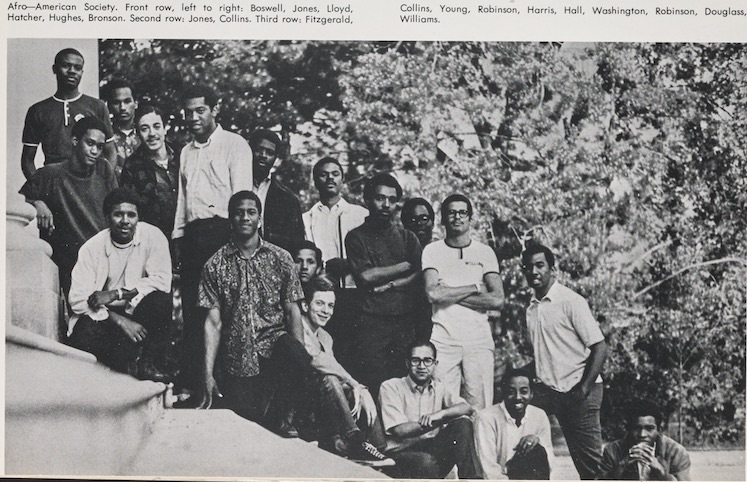

The Williams Afro-American Society in 1968

The Class of 1968 experienced African Americans’ growing anguish and benefited from the seeds of change that had been planted by earlier generations. It is fair to speculate that this class comprised the most anticipated group of black students since integration began at Williams (and before coeducation). Williams boasted its largest black enrollment to date: five students. These Class members are Adriel Bowman, Sterling Green, Sherman Jones, Sterling Lloyd, Jr., and William Silver .

By their senior year, the Class of 1968, along with the rest of the world, registered the shock of four assassinations, beginning with the assassination of Malcolm X, the once-militant spokesman for Black Islam turned moderate political activist. While the majority at Williams did not seem affected by his death, black students felt that the assassination represented a depreciation of black American leadership and interests.

Violence seemed to intensify in the world outside Williams with the Tet Offensive in Vietnam in January 1968. The nation watched as thousands of college age men were sent overseas. The campus responded with vigils and prayers for friends and family members who were being sent to fight a war in a nation which few could find on a map.

The campus was shaken by despair once again when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a man who epitomized the ideals of nonviolent protest and racial brotherhood, was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. Williams students—black and white—prided themselves on applying King’s methods of passive resistance and nonviolence. However, after his death, some of the blacks at Williams questioned whether practicing nonviolence was the solution to African Americans’ problems. One black student expressed such feelings when he said, “Militant, more aggressive moves will play a bigger part in this movement.”

Sherman Jones, Williams College Class of 1968

Sherman Jones ’68 expressed his feelings about Williams bluntly, calling it “an unnatural choice,” and summarizing the Williams experience for blacks at that time as “lonely and isolating.” Despite his feelings, Jones led the relatively new WAAS during this confusing period. Although tempted to initiate strong action on campus in response to King’s death, initially he spoke against the sit-ins and boycotts that many other black organizations took part in at other colleges. WAAS members were particularly close to members of the faculty and administration and decided to use alternative means of protest only as a last resort. Jones called for the development of various programs that would benefit Williams in the spirit of Dr. King’s life and work. These included:

- a history department chair that would develop and promote in-depth study of blacks in America

- a Martin Luther King Memorial Library that would house Afro-American writings and other materials

- a winter “A Better Chance” program dedicated to preparing disadvantaged high school students for preparatory school and college

- funding to support the functions of the WAAS.

The most immediate of the proposals—funding for the WAAS—was undertaken immediately, due to the diligence of WAAS members, who donated $1,000 of their own money to the cause. Fundraising continued with Martin Luther King benefit concerts and donations from the College Council and the Gargoyle Society.

(Of the four proposals Sherman Jones laid out following the King assassination, only one—WAAS funding—was adopted. His remaining proposals were renewed by others at the time of the occupation of Hopkins Hall a year later. )

Although the WAAS had succeeded in bringing positive action to bear in the wake of the tragedy of King’s death, feelings of stability on campus would be short-lived: on 4 June 1968, mere days after graduation, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated while campaigning in Los Angeles. The Class felt that its journey through Williams had ended as it had begun: it had been only five years since John Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. But despite the turbulence of their time, the five black graduates of 1968 went on to become distinguished alumni. Sherman Jones set the stage for success as chairman of the WAAS and graduated with honors in American civilization.

The project paper ends with this concluding statement: Well over a hundred years have passed since Gaius Bolin, Williams’ first black student, joined the ranks of his fellow freshmen in 1885. Since then, hundreds of talented young people of African descent have passed through the halls of this institution, most as students, others as educators. While here, and in their lives after graduation, they have applied themselves both to their studies and to serving their communities with diligence and consistency.

As this document shows, their tenure here has at times been an uneasy one—and sometimes ridden with tensions. Not even the “Purple Bubble” is immune to race issues; it has seen its share of upheaval and misunderstanding. But there have been many moments of triumph when the entire campus has banded together to celebrate the accomplishments of the many students, faculty, and staff of African descent who achieved excellence here, and who have since continued their excellent work all over the world.

It is to preserve and celebrate the history—both the bitter and the sweet—of black students at Williams that students took on the research and writing for this project.

Editor’s note:

If you haven’t already seen it, please read classmate Peter Miller’s moving account of our efforts to bring Martin Luther King to our campus.