During the month of January 1968, Associate Professor of Anthropology Thomas Price guided a group of seventeen Williams undergraduates to the Island of Roatan or (or Roatán, to use the Spanish spelling) for hands-on experience with the rudiments of anthropological research.

From our class, Guy Horsley, Skip Edmonds, Bob Gault, Scott Wylie, Peter Naylor, Curt Tyler, Al Bartovics, Steve Bradley, Bob Lord, and Alexander Caskey were part of the group, although there may been more 68ers. Let us know if we’ve missed anybody.

The Bay Islands of Honduras (formerly of British Honduras, now Belize)

Closer view: there are three islands, Utila, Guanaja, and Roatan (the largest) where we stayed.

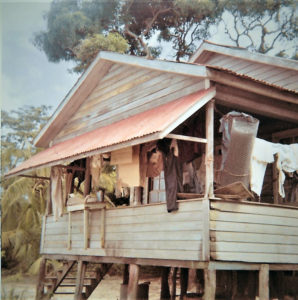

Today these islands are a haven for snorkel and scuba divers, with luxury hotels and accommodations having displaced the typical island house built on stilts over the water in which we spent the month of January of 1968.

The experience — overview

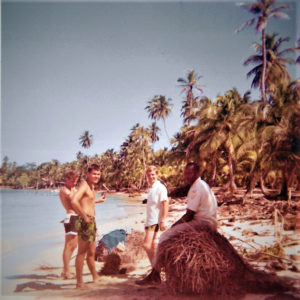

We lodged with families, ate with them, went to church with them, and opened ourselves to a new and different culture. It did not hurt that we experienced Caribbean temperatures and were able to swim and snorkel in warm waters.

The Islanders (as they called themselves) were all of African descent, but despite Honduran rule, they stuck fiercely to the English language they had spoken for years before the islands shifted from British to Honduran rule. Many of the men shipped out on United Fruit boats, some had been as far as Vietnam (one resident of Sandy Bay owned a small store with a map of Vietnam showing the location of the small store he’d owned there). Several of the women had also spent time away, most as caregivers and nursemaids in wealthy American suburbs.

You’d have expected musical tastes to incline toward Caribbean rhythms, but American Country Music (especially Buck Owens) was the favorite. In fact, one islander introduced us to the location of the Hillbilly Ranch, on Park Street in Boston, for years the haven of the Lilly Brothers and Don Stover. And we indeed went there to check it out.

The English spoken had several levels. You could accompany and participate in most conversations but when Islanders wished to communicate privately, they leaned back to a less decreolized version of the language, and we were challenged to keep up.

We kept busy with our individual projects (one was to collect folklore and capture observations on linguistic features of Island English), and we all had to find subjects to complete a questionnaire that was 90% innocent. The remaining 10% ventured into intimate territory and bedtime practices and left several of us quite nervous. But we did it. And were graciously accommodated for the most part. See Guy Horsley’s account in particular about this aspect of our research.

Individual accounts by 68ers

(Don’t miss Guy Horsley’s full account at the end)

Bob Lord:

Just a few memories of the experience: 1) I was dropped off on a beach and moved in with a mother and her three children in a very small, 2 room house (read “shack”) on stilts just off the beach. (Her husband was on a tramp steamer somewhere in the Caribbean). The toilet and kitchen were on the ground level a short walk away. (Reason: one for sanitation, the other for fire hazard). At night the chickens and a pig or two sheltered under the house. What a racket. More significant was the fact that about 6 months after returning home, I suddenly discovered, in the obvious way, that I was home to a growing family of tape worms. Fortunately, Western medicine took action to quickly resolve the “problem.” On a good note: with the only kerosene lighting at night being at the 1 room church, all gathered most evenings for song and socializing and provided an ideal opportunity to work through the questionnaires.

Bob Gault:

I lived first in the main village [Coxen Hole]. Didn’t work out as the son with whom I shared a “bed” played his portable radio all night. I recall hearing “Ici radio de la patio” ( phonetic) broadcast repeatedly all night. I moved to Flowers Bay, I think about 5 miles down the path. That was good place. Was a good round trip walk to the bar every day to savor warm beer with whoever showed up from our group.

I only recall there being the tiny wood houses. And of course no plumbing.

I recall one of the group made a movie of parts of the trip: “You say. Hello; I say goodbye”: after the way the locals spoke when passing on a trail. (Credit to the Beatles).

I was very isolated tho that was fine. No other Williams classmates close. Did walk into “ town” about once day as indicated to have a beer and chat generally with Pete Lammertz (rip) and Dave (can’t remember last name). Did some snorkeling with them and fishing with Eric, a local boy about 10. Caught huge moray eel 5 ‘ or so that I thought might chew me up. Lammertz speared a fish while out snorkeling. Speargun. Blood all around us. Scared the hell out of me. I never swam so fast to get out of there. Barracuda all around and who knows what else.

I brought back a parrot, Queequeg (see above), a female as I later learned, lived with me for 12 years. Semester at Williams in the Zoo, Thru UM law school, 2 year clerkship in Seattle and in Mass In various places. Passed away suddenly one evening in late ’80. Was a great companion and in those days I could take her in bars which I did regularly. Bought her on one of the neighboring Bay islands for $5, cage included. She loved beer and, perched on my shoulder, would grab my glass, pull it over to her, drink and then laugh.

Peter Naylor:

I stayed at Sandy Bay with Kellogg Smith and his family — his wife and three grandchildren. Kellogg was a retired merchant seaman and very intelligent.

He read anything that he could get his hands on.

The grandchildren had lost their father exactly a year before we arrived, and Kellogg said that I was his twin. The kids would climb all over me, while Kellogg and I discussed world affairs. Kellogg said,” Kids are like dogs. If you pat them, they’ll climb all over you.”

The boys’ mother worked as maid in NYC, but was home briefly for the holidays, (overlapping a few days with us).

The Smith’s home was well made, set ten feet above the ground on stilts.

Water was piped from a well a few hundred yards inland. Their toilet was an outhouse fifty feet out over the water.They had parrot who could imitate the grandmother calling the boys. When the boys would come running, the parrot would imitate Kellogg’s laugh.

When we first arrived, (Prof) Tom Price bought a piglet, which I fed daily until the pig was slaughtered and served for a bar-b-que.

My assignment was to study the local economy which had been based on banana exports

prior to the development of large plantations on the mainland. (There had been a US Consulate in the island in 1900).

When we were on Roatan, there was little tourism. I called it, “a male export Economy” in which men worked in the US and sent funds home for the construction of family homes and maintenance of their families. In some cases, one brother would stay in the island to look after the extended family, while the others worked in the US. (Later, I encountered one islander driving a taxi in Oconomowoc, Wisc.)

Scott Wylie:

I too was part of this group and lived with a family on the airport side of the island on the edge of Coxen Hole. My host was Daniel Scott which gave rise to all sorts of joking about our shared first/last name. Among Daniel’s pursuits was a traveling salesman business. He went door to door selling household goods all over the island. I offered to go along with him on one of his selling trips and carry his sample suitcases. We made quite a picture as I towered over him and many of the customers couldn’t quite believe their eyes. Given that there were really no roads, we hopped on boats and dugouts to get around.

I spent hours with the local children and teenagers asking about their lives and families. I recorded hours of so-called “Nancy Stories” which are folk tales passed down verbally generation to generation and are revealing clues about culture.

I have returned three times and recently reunited with Daniel Scott’s widow which was a real treat.

I do remember one or two bottles of warm beer (no electricity = no refrigeration = warm beer)

It was an eye opener of an experience all around.

Alexander Caskey:

I was in Sandy Bay, on the other side of the island from Coxen Hole, where the planes landed and took off to La Ceiba. An American family named Adams from Iowa had just showed up there and were getting some funny looks from the islanders but it was clear that they were out to alter that small piece of paradise forever. As I recall, there was talk of setting up a hotel for gringos with a slant toward scuba/snorkel tourism. Guess what happened next.

Bob Lord was just down the beach from me. We used to puzzle over the expressions the islanders used when greeting someone coming the other way.

Going up? The answer would be Going down. We could never figure out which was up or down. It seemed they changed them on us. Maybe directions followed the tide. Any time we tried, we got it wrong and were corrected.

One guy had a little store (shack) where you could buy beer, pop, and household supplies, etc. On the wall was a map of Vietnam where he’d had another store for many years. Guys traveled everywhere, boats from United Fruit.

If you bought something, they’d quote you a price in lempiras (national currency of Honduras) and then halve it if you paid gold (dollars). 50 lempiras, 25 gold.

There was a VERY powerful local firewater they called casousa. Made from cane, like the cachaça of Brazil. Heavy duty. I know this because Chester Connor (see below) just about always had a bottle of it handy.

My task was to document folklore and language. No tape recorders were available, so I transcribed a lot by hand. Got some great stories and learned a lot about the variety of English spoken on Roatan. It would not be wrong to say that this experience is what led me to become a (academic) linguist. One of the names I took down was “mamee apples,” a great fruit which I also got served a lot.

I stayed in house like the one Bob Lord describes and shown in Guy’s photo. Miz Fel Connor (in her early 60s) was the occupant although she had a husband, Chester Connor, who would show up now and then, usually blasted on casousa.

Miz Fel had an entirely different orientation. Since there wasn’t a great deal to do in the evening (no electricity), she’d invite me to go to church. Depending on the church we went to, I’d run into Rob Lord, who got to be pretty good with the hymns. It didn’t seem to matter which church you went to, Pentecostal was one of the options I remember, and you could choose freely. Pastors were locals, often the guy you bought a bottle of soda from earlier that day.

Miz Fel would serve my dinner every day, on one occasion asking me if I didn’t mind eating “barrafish.” What? Another word to write down. It turned out to be barracuda, and the one time I went snorkeling, there they were, staring at me. I said, Going up?

Guy Horsley:

Informal notes:

From my notes it appears that Skip and I were the first assigned to the west end, but at least one other joined us later. I cannot remember much of anything outside of my notes (names or faces), but the name that shows up is Steve Bradley – my notes from January 4 reflect we attended a church service at Half Moon Bay “with Steve Bradley who had just arrived at Half Moon Bay to stay with Hoare’ Wood and family.” I didn’t record any other student as having been assigned near us but it could have happened. One mystery name that shows up in my notes is “Steadman” – but I do not know whether this was a west end resident or student – my guess is he was not one of us (?)

With more to come…

Guy’s full report:

A. Introduction

I was fortunate to be the only (paid) student assistant to Professor Price, Williams College’s one man Department of Anthropology in 1968. The job put me in the prime position to accompany him and other students on the January 1968 Winter Study expedition to Roatan Island, a Caribbean island belonging to and just off the coast of Honduras. He chose this locale for our anthropology study project, in part, because the residents’ primary language was English, and they were receptive to hosting our group (for not much money). Roatan formerly was part of British Honduras, which is now Belize.

My friend, Skip Edmonds, also signed up for the expedition (Skip, like me, was from Richmond, Virginia, and we had roomed together during our freshman year). We arrived on the island on January 1 before the rest of the group and were given our choice of host families. We chose the west end of the island, the most remote and beautiful part of Roatan, while most of the other students were assigned along with Dr. Price to live with families nearer the town or in more populated areas. There were several host families from which we could chose, and, on the flip of a coin, I won first choice. Of course, I chose the family with a house on the beach, on stilts, with a terrific view of the ocean. Skip’s family lived off the beach up on a small hill.

B. First Impressions

My hosts were an older couple, Paul and Serena Ebbans, who had no resident children. Their stilted house consisted of four rooms and a front porch looking out to sea. It was near Half Moon Bay, an unspoiled picture postcard perfect bay with white sand beaches, surrounded by palm and coconut trees. This part of the island was thinly populated; only a few houses could be seen from the Ebbans’ house, none of which were so beautifully situated.

The Ebbans gave me my own bedroom and prepared my meals, eating separately from me. They were extremely kind and eager to please me. My first meal – lunch – included meatballs, cheese spaghetti, beans with rice, fried potatoes, potato salad with chocolate cake for dessert, all prepared from scratch by Serena. Meals were consistently good (although I got a little tired of the omnipresent coconut oil).

One of the best indicators of the hospitality of the west end residents was that they constructed a wooden outhouse for the exclusive use of the students at the end of a pier. I assume they used the woods as their bathroom.

I don’t know what was the Ebbans’ impression of me, but I was favorably impressed by them and felt at ease with them. They were at the top of their social ladder, in part because of their financial success. He was a fisherman and farmer; she operated a small “general store” selling some groceries and various hardware/kitchenware items. Also, they were relatively light skinned, and skin color was definitely a consideration in social status among the residents.

I was naïve in my expectations about the island residents and their life styles, envisioning them to be fairly primitive and unsophisticated by our USA standards. While the west end residents had neither plumbing nor electricity, they managed to live comfortably. The Ebbans, for example, had kerosene lanterns for light, an efficient kerosene refrigerator (I didn’t know there was such a thing), and a four-burner gas stove. They were cooled by ocean and bay breezes. Paul Ebbans had a dory powered by a small gasoline engine; he used it for fishing and traveling to town and other island locations. Serena was an excellent cook; she baked small loaves of white and raisin bread, selling what we didn’t eat from her general store.

Residents were relatively well informed about world events, despite the lack of televisions or regular newspapers in the west end (they had battery operated radios). My hosts, and many others, were fairly conservative in their political views and many supported an aggressive U.S. stand in Viet Nam.

C. Adventures in Paradise

Shortly after I arrived, I arranged to rent a small horse from Paul who borrowed a saddle from one of the residents. Skip had also rented a horse; we had to go to town to check in with Professor Price. The cost of the rental was about 2 or 3 dollars. Mr. Ebbans teased me by telling me how much more this horse rental would have cost in Central Park in New York City (he suggested $35; so much for thinking he was an unsophisticated native!). He apparently had a nephew living in New York.

To get to town, we rode for about an hour over rough terrain, through both swampy and hilly country. Skip’s horse threw (and then kicked) him, but we finally arrived with the help of two young boys who guided us to town where we met with Dr. Price and the other students.

Two days after Skip and I arrived, we were invited along with several others to attend an evening church service at the west end’s Baptist Church. When we arrived, we were asked to sing a hymn – we chose “Rock of Ages” – to the delight of the congregation. Our singing was terrible, but it helped to break the ice and introduce us to the local population.

Looking over my daily log, it is apparent that I did more recreation than study, but I still managed to learn much about Roatan and myself. Skip and I fished, scuba dived for lobster, explored the island and formed good relations with the residents. During the few times we came to town, we went out with the other students to enjoy the local beer bar, socialize and play cards.

I had a close encounter with a large (at least he looked large to me) hammerhead shark while I was snorkeling near the beach. Luckily for me, he was just slowly cruising along and glided right over me. Other fish that I remember included barracuda – they were more aggressive than the sharks, so we learned to fear them even though they couldn’t really eat us.

We were careful throughout the winter study project to avoid being “ugly Americans,” showing respect and appreciation towards our hosts. We did run into one ugly

American, however, at a hotel in town, where he and his wife – or companion – were guests. The “hotel” was a wooden building, the interior walls of which were thin. The man loudly and drunkenly badmouthed everyone, including us, and we could hear his rantings throughout the hotel for hours.

I tried to show my appreciation to my hosts and to avoid any insensitive comments or behavior. My biggest challenge in this regard came about through my own fault. Mr. Ebbans told me he was going to butcher a bull calf, and although the meat itself was not good, some of the organs were popular with the residents, particularly the liver. I mentioned to him that as a boy I had “kidney stew” from an old family recipe (of English origin no doubt), so I could understand that the calf’s organs could be good for food. This turned out to be a big mistake because soon thereafter, Serena Ebbans presented me with the boiled and otherwise not disturbed beef kidney as a big surprise. Was I surprised? Indeed, but I could not eat that thing nor could I insult her by telling her so. Luckily, I was left by myself to deal with the kidney. Good luck stayed with me, because I heard a distinct “meow!” from under the table and I met my new best friend, the Ebbans’ cat who got a meal for himself and me out of a big embarrassment.

Good luck was not with me regarding my health, however. I came down with what I thought was a cold, which turned into a high fever. I went to town to be examined by our project doctor Dr. Mersailles (sp?), who diagnosed some type of viral pneumonia. Never shook it completely, and it was a downer – literally. I spent several days in bed during which Serena gave me what medication she had (aspirin and Ben Gay) and otherwise took care of me. Upon returning home, my family said I looked like a returning prisoner of war!

D. Winter Study (?)

We did do some studying despite the impression one might get from reading the foregoing. In addition to learning by observation about Roatan and its residents, we were given specific and individual assignments/projects by Dr. Price. My projects involved (1) a study of how the economy of the west end residents was related to that of the outside world and (2) a study of the sexual practices of the residents.

The residents were most agreeable to talk about sex, so my initial embarrassment was eased. One of my interviewees was a 76-year-old man who bragged to me about his sexual power in fathering a baby to whom I was introduced along with its young mother. Homosexuality was frowned upon, but male/female sexual behavior was both encouraged and enjoyed – privately. I have no recollection about my report on the economic topic.

Professor Price held periodic “classes” to review the progress of our studies, to which we would travel and compare our experiences. We were told to keep a daily log of our experiences and impressions, and to report on our individual projects at the end of the program.

E. Final Impressions

Despite my struggle with my tropical fever, the Roatan Winter Study Project was a highlight of my life and a great learning experience (although not particularly “academic”). I think our students, generally, behaved well and earned the respect of our hosts. Our project doctor teamed up with an American dentist who was there to provide a free clinic for the residents, who lined up appreciatively, especially for the dental care. We not only studied the lives and cultures of the residents of Roatan Island, but formed friendly relationships and developed mutual respect with them. Thanks to Williams College and Professor Price for this great opportunity.

Editor’s note:

Thanks, Scott, for getting touch about Roatan.

We’ve moved the body of Scott’s account to the main report (https://williams68.org/roatan-january-1968/), please do check it out

I too was part of this group and lived with a family on the airport side of the island on the edge of Coxen Hole…

Wonderful article! What an amazing trip and a testament to the excellent educational opportunities at Williams.

I’m a grandson of one of the family and I would like to get have more info..anything little thing would b appreciated,#tolowood#downtheroad