Fifty-two years ago, on the night of April 8, 1969, a group of antiwar Harvard students, led by members of S.D.S., the Students for a Democratic Society, marched to the home of Harvard’s president, Nathan Pusey, and tacked a list of demands to his front door. The demands ranged from the abolition of R.O.T.C. on campus to lower rents for university-owned apartments in the city of Cambridge. The next morning, April 9th, thirty supporters of the demands entered University Hall, an administration building in Harvard Yard, and forcibly ejected administrators and staff. A photo of the protesters bodily carrying one dean out of the building made the front page of nearly every national newspaper. Once the occupiers had taken over the building, they chained the doors shut. The Boston Globe reported that by evening there were more than five hundred people inside University Hall, determined to support and protect those inside.

In the spring of 1969, I was a graduate student in the Harvard Soviet-studies department. Along with many others, I watched the occupation from the steps of Widener Library, where I regularly studied in the stacks. I agonized over whether to join the protest. At times, I would mill around the edges of the crowd that had gathered outside University Hall, now and then holding up a sign that someone handed me. But the moment I sensed that something bad might be about to happen to the protesters, I gave back the sign and retreated to the library steps, only to rejoin the protest a while later, when it became clear that there was nothing to worry about, then back to the library when I again sensed trouble. This back-and-forth dance of mine went on for hours. The reason for it was fear. I wanted to participate, but I was afraid that if trouble started and I got arrested and thrown out of school I would automatically forfeit my precious student deferment, which, as I saw it, was the only thing standing between me and an early death in the jungles of Vietnam.

It is ironic—you might say, moronic—that, less than two months later, I voluntarily gave up that deferment, dropping out of grad school in a moment of monumentally short-sighted pique fuelled by my long-simmering desire to change the direction of my life and become a cartoonist before it was “too late.” (Only a twenty-two-year-old could think that twenty-two was almost too late.) I also yearned to join the wild party going on all around me in Cambridge, where everyone but me seemed to be blissfully losing his way—enjoying free time, free love, and the free tabs of acid on offer every weekend on the Cambridge Common.

But all of that, including a frightening but brief encounter with the Selective Service System, was still in my future in the early evening of April 9th, as I gave up the struggle and slunk away from the still-raging demonstration, leaving Harvard Yard by the only gate open to the street. Rumor had it that anyone who remained would be arrested for trespassing.

I returned to the Cambridge apartment on Green Street that I shared with a constantly shifting cast of five to ten roommates. Some were students, others were dropouts—with one or two, I never found out exactly who they were or what they did. Two roommates were members of S.D.S., including a friend from my high-school days whom I will call Bruce, a tall, lanky, baby-faced Harvard dropout who made a living dealing pot.

Between the partying, the endless comings and goings, the competing stereos, and a band called the Dead Skin that rehearsed day and night in the building directly across from my room, the noise in the apartment was relentless, which was why I mostly studied in Widener Library and slept at my girlfriend’s place when I could. She lived across the street, next door to a building where members of the then famous Jim Kweskin Jug Band lived at the time.

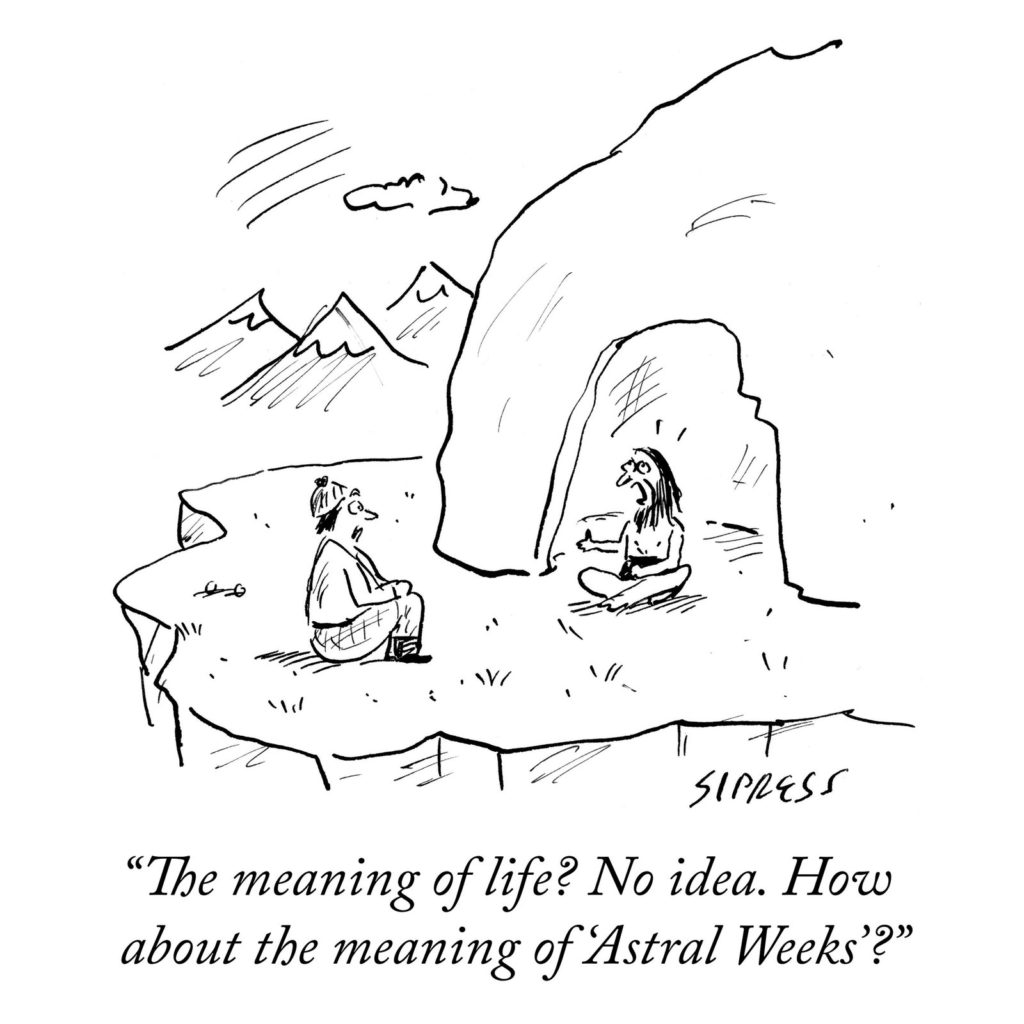

On the nights that I slept in my own bed, I would slap on headphones and lull myself to sleep by listening over and over to the hypnotic, poetic, wonderfully cryptic album “Astral Weeks.” (Once, while tripping, I became thoroughly convinced that the tune “Cyprus Avenue” was a secret message from Van Morrison to me, David Sipress.) Back then, I would tell anyone who would listen that “Astral Weeks” was the greatest rock album ever made. I’m still slightly obsessed with it today.

Much later, long after I left Green Street, I found out that Van the Man had been living right across the street from me that whole time, in the same building as the Jug Band.

After I got home from the demonstration, I watched a little of the coverage on the tiny portable television that we kept on the kitchen table. After a typical dinner of Rice-A-Roni and a bowl of Grape-Nuts for dessert, I decided that I was too jazzed from all I’d seen and heard that day to study. To calm myself, I smoked a joint, read for a while, and got into bed, eventually falling asleep, as usual, to “Astral Weeks” playing in my headphones.

Next thing I knew, Buffalo Springfield was exploding inside my brain: “There’s something happening here / what it is ain’t exactly clear.” I ripped off my headphones. A grinning Bruce was standing by my turntable, one hand on the volume knob, the other raised in a triumphant fist above his head. It was just after dawn. He jumped on my bed and started breathlessly filling me in. “Around three o’clock, a massive number of pigs showed up,” he said, “all in helmets with visors and carrying billy clubs and cans of Mace. It was Chicago all over again. They hauled people away from outside the building and then went after the guys inside. That’s when I ran.”

He had barely escaped arrest, but many others hadn’t been so lucky. A roommate who had stuck it out with Bruce was one of more than a hundred protesters arrested for trespassing. Several people were even charged with assault and battery. In the coming days, most of the charges were dropped, but a number of protesters were tried and convicted, and ordered to pay fines. Two of the occupiers were sentenced to nine months in jail. Twenty-six Harvard students were expelled.

Watching the morning news with Bruce and my other roommates in the kitchen—eating Grape-Nuts again, for breakfast this time—I tried to keep the guilt over my own inaction at bay by reassuring myself that I’d made a sensible decision to avoid arrest, expulsion, and the Army. Mostly, though, I felt angry. We all felt angry. How could the university invite in the cops and their Gestapo tactics? How could they condone beating and arresting peaceful demonstrators? Things at Harvard had to change. Things in the country had to change.

And things did begin to change—at least at Harvard. There were further demonstrations, several mass meetings, and a successful student strike, all leading to real changes in the university’s R.O.T.C. policy, as well some progress in the way Harvard did business and conducted itself in the community. That was the thing about those turbulent years: during the late sixties and early seventies, you felt angry and afraid much of the time—but never hopeless. It seemed inevitable that things would get better, that the marches, the protests, the bravery of those who risked beatings and arrest would inevitably get results.

Sadly, these days, living in Trumpland, I’m finding it increasingly difficult to find that kind of hope.

Thank goodness there are others more optimistic than I am, people willing to engage in civil disobedience like the occupiers of University Hall fifty years ago. True to form, I have limited my involvement to marching, writing letters, giving money, and, of course, drawing political cartoons—none of which is particularly risky. But I suppose that even these modest activities indicate that I still have a bit of hope.

The morning after the occupation, I returned to Harvard Yard to see what was going on, and to try to work in the library, but when I got there the Yard was still closed. A crew from a Boston TV station stood in front of one of the locked gates. Spotting my work shirt, my tatty blue jeans, my engineer boots, and my massive Jewfro, a female reporter with a blond hair helmet approached and asked if I had been part of the demonstration.

“Sort of” was my honest reply.

She wondered if she could ask me a few questions, and I agreed. She stuck a microphone in my face, and, after a few preliminary questions, the interview went like this:

She said, “We heard that radicals from S.D.S. engaged in acts of violence during the protest in Harvard Yard yesterday. What do you know about what went on in there?”

At this point, the camera shifted away from the reporter to the now peaceful scene beyond the locked gate, where it remained while I gave my reply.

“That’s not what I heard,” I said. “If it’s true, I’d have to say that I’m totally against the use of violence, including by S.D.S. But, from what I heard, the only real violence was done by the police. I hear it was awful in there.”

Then I ended the interview, suddenly uncomfortable, and worried that I might have said too much.

That night, my roommates and I again sat around in the kitchen watching the news, hoping for updates on the protest. Suddenly, there I was, my explosive hair taking up two-thirds of our minuscule screen.

“We heard that radicals from S.D.S. engaged in acts of violence during the protest yesterday,” the correspondent said. “What do you know about what went on in there?”

As the camera moved to take in Harvard Yard, we all listened to my reply:

“ . . . I heard. . . . I’d have to say that I’m totally against the use of violence . . . by S.D.S. . . . I hear it was awful in there.”

“What the fuck?” I shouted.

Everyone glared at me, looking like they wanted to kill me. I babbled and pleaded, trying to explain that my words had been totally twisted, my true meaning reversed. Giving me the finger, Bruce told me that whatever I said or didn’t say, I was an asshole for talking to the media when I hadn’t even had the guts to join the protest.

I was eventually able to convince my roommates and a few close friends that I’d been misquoted. But, for months afterward, total strangers would stop me on Mass Ave. or in Harvard Square and furiously berate me for my cowardly, bald-faced, fascistic, anti-revolutionary lies about the occupation of University Hall. What could I say—that it was complicated? That things aren’t always what they seem? Mostly I wound up mumbling that I was sorry and then hurrying away, looking for all the world like someone guilty as charged.